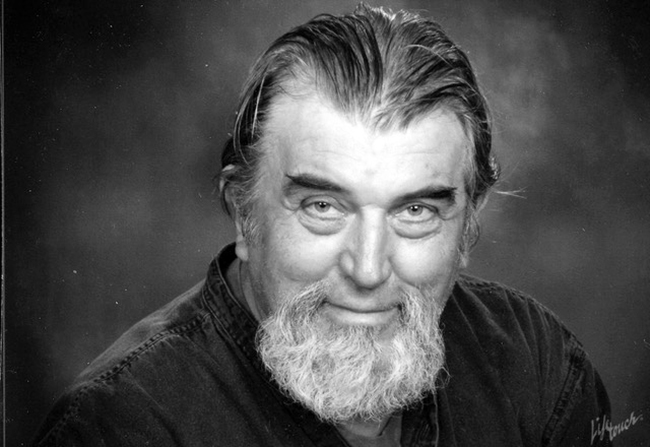

Louie Robinson: Celebrated journalist

Pioneering journalist Louie Robinson died of heart failure on October 2, 2015 at Northwestern Memorial Hospital in Chicago, two days shy of his 89th birthday. He had lived in Claremont since 1963.

Mr. Robinson wrote for Ebony for three decades, serving as the magazine’s west coast editor for much of that time, as well as contributing to publications like Jet and Negro Digest.

“If you open up an Ebony from the 1960s to the mid-1980s, you’ll see something written by my dad,” his daughter Robin Robinson said in an obituary published in the Chicago Sun-Times. “There were times when three-quarters of the content was written by my dad.”

Mr. Robinson was an author as well, with the books Arthur Ashe: Tennis Legend (1967) and The Black Millionaires (1973) to his credit. He co-authored Nat King Cole: An Intimate Biography with the late singer’s wife Maria Cole and helped Sidney Poitier prepare his memoirs.

“Never in my life have I known a better man,” Mr. Poitier said in an Ebony tribute. “His life was an experience that will leave behind memories of major importance. In his life, from which many humane experiences have arisen to the benefit of so many of his fellow human beings, he has always stood strong and he has always reached out to those in need.”

Most often, Mr. Robinson reached out through writing.

During his tenure with the Johnson Publishing company, the pages of Ebony and Jet teemed with his sprawling profiles of luminaries like Diana Ross, Nancy Wilson, Quincy Jones, Sammy Davis Jr., Harry Belafonte, Richard Prior, Redd Foxx, Wilt Chamberlain, Ray Charles, Ella Fitzgerald, Jackie Robinson, Marlon Brando and the Jackson family.

“Robinson defied the odds during a time when America denied the existence of Black excellence,” the Ebony piece emphasized. “Through his work, the journalist showcased some of the nation’s most famous symbols of Black achievement.”

At times, his willingness to tackle any subject led to a touch of danger. In a September 1965 edition of Jet, Charles E. Brown recounted his experience covering the recent Watts riots. The unrest lasted six days and resulted in 34 deaths, 1,032 injuries, nearly 4,000 arrests and the destruction of $40 million of property.

The rioting started on a Wednesday. On Monday, the reporter suggested that Mr. Robinson, who was the publication’s west coast bureau chief, accompany him on a tour of the riot zone. The men had passed five National Guard checkpoints and had just passed the intersection of Avalon Boulevard and Slauson Avenue when 30 police cars pulled up.

The officers exited their vehicles and began shooting at an apartment building, eventually drawing out 40 to 50 people. “For 15 minutes, the gun battle ensued,” Mr. Brown wrote. “When the shooting subsided, Robinson and I got up off the floor of the car.”

Mr. Robinson’s willingness to track a story to the source also came into play in a matter involving a musical giant’s reputation.

In 1957, the tabloid Sepia ran an article called “How Negroes Feel About Elvis.” Elvis Presley was painted as a racist and quoted as having once cracked, “The only thing Negroes can do for me is shine my shoes and buy my records.”

When Mr. Robinson interviewed Mr. Presley on the set of his movie Jailhouse Rock, he was unequivocal: “I never said anything like that, and people who know me know that I wouldn’t have said it.” Mr. Presley’s black colleagues, who said he viewed the person, not their color, supported the statement.

In several hundred words, Mr. Robinson had cleared the King’s name. His own story started in Dallas, Texas, where he was born in 1926. He grew up in the town of Mineral Wells and was raised by his mother Bessie, who was a domestic worker. His grandfather J.U. Wyatt, a longtime waiter at the Baker Hotel, helped support the family.

He also provided his grandson with “the once-a-week 15 cent admission to the Gem Theater’s balcony (especially reserved for those of my color) and an inevitable bag of gum drops,” Mr. Robinson wrote in a 1971 article about returning to his hometown.

Young Louie developed a hankering to write early on. He was a voracious reader of newspapers and had been encouraged by an English teacher. His mother laid the foundation for him to follow his dream by insisting he learn to type; she hoped the skill would lead to “inside” work for her son.

He left town when he was 16 to seek his fortune. In the Ebony story, Mr. Robinson wrote about why he escaped Mineral Wells.

“The place had been reasonably kind to me as a child, in the indulgent way that some Southern towns can be kind to black boys,” he said. “But I saw its approaching cruelty—that time when, as a man, I would find myself still confined to a boy’s work: shining shoes, cleaning up barrooms or being a handyman at something less than a man’s wages.”

He enrolled at Lincoln University in Missouri, the only black college in country with a school of journalism. His studies were interrupted when he was drafted into the army in 1945 during the end of World War II. During basic training, he was assigned to a group of combat engineers, until one day his supervisor asked if anyone in the outfit could type. Mr. Robinson spoke up and as a result remained in administrative posts until he was honorably discharged.

When he left the army, rather than returning to his studies, Mr. Robinson became involved in the startup of a weekly paper called the Tyler Tribune in Tyler, Texas. He later earned an honorary degree from his alma mater of Lincoln University.

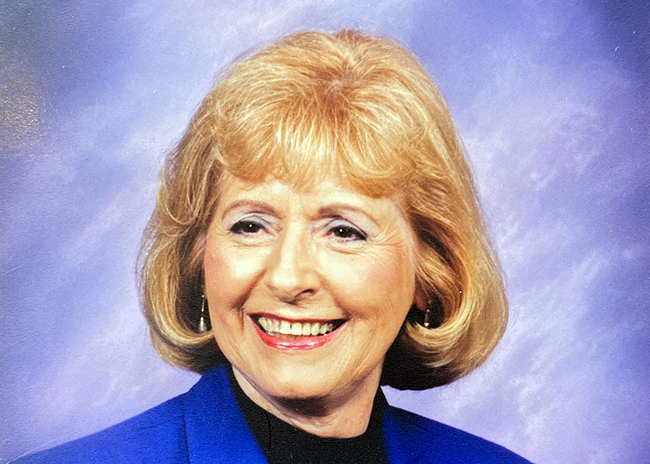

A young woman named Mati attended a reception for the newly launched publication where she met Louie. They hit it off and were married in 1951. After two years, the newspaper was doing so well it was bought out, moved to Dallas and rebranded as the Dallas Morning Star.

Mr. Robinson next worked for The Afro-American in Baltimore. Before long, he was recruited by John H. Johnson as a writer for Johnson’s Publishing. The company produced Ebony and Jet, groundbreaking black news magazines with a national audience.

In 1960, Mr. Robinson was asked to relocate to Los Angeles to manage the publishing company’s west coast affairs. The family moved to California, settling in Pomona in 1960 and Claremont in 1963.

Mr. Robinson would head to his Beverly Hills office to gather news. Then, he would return to Claremont, where he’d type his stories in his home office. “You could hear the tapping of his typewriter,” Mati recalled. “When he began using electric, it was pretty noisy.”

The Robinsons’ first child, a daughter named Robin, was born in 1957. She went on to become a noted news anchor and radio host. In the Chicago Sun-Times obituary, she marveled at how, “His fingers would fly across the keyboard, and words with no errors would fly across the page.”

Sometimes the Robinsons would use their home to quietly entertain people they met through the business, folks like Sammy Davis Jr., Nancy Wilson—who remains a family friend—and Arthur Ashe, who convinced Louie and Mati to start playing recreational tennis. Other times, the pair headed out to industry events, including a dozen Academy Awards ceremonies. Ms. Robinson had a formula.

“I had a little black dress I wore everywhere,” she told the COURIER. “I knew better than to try and compete.”

Mr. Robinson loved what he was doing and always felt he was making a difference.

“I think that was the success of the Johnson Publishing company, that they tried to cover the whole country—what was going on at the time with integration and segregation,” Mati said.

Locally, Mr. Robinson taught classes in communications for the Claremont Colleges’ Black Studies Center for several years. The Robinsons were also active in the Claremont community at large, where three of their six children attended Claremont High School. They were co-chairman for the Community Friends of the Claremont Colleges and twice served as co-presidents; they were given the organization’s “Volunteers of the Year” award for their efforts. They enjoyed relaxing by playing tennis and golf.

COURIER publisher Peter Weinberger remembers the Robinsons as regular guests at the Weinberger home. “Louie and Mati could talk politics with my father, Martin, for hours outside by the pool. Even after dark, I could still hear them, just not see them.”

Right up to the end, Mr. Robinson retained his characteristic humor, Mati said.

“He had been at death’s door two or three times. He knew he wasn’t going to recover,” she shared. “On the day he died, he said, ‘A funny thing about this: I have a habit of not dying when I’m supposed to.’ He made it as easy as it could be on the rest of us.”

Mr. Robinson is survived by his wife of 62 years, Mati; four of their six children, Toni Frazer, Michael Robinson, Robin Robinson and Stacy Robinson-Hinkhouse; son-in-law Lou Hinkhouse; 10 grandchildren, 12 great-grandchildren and five great-great-grandchildren.

A memorial service in Claremont will be planned for the spring.

—Sarah Torribio

storribio@claremont-courier.com

0 Comments