Pomona professor: ‘pay it forward’ to solve state water woes

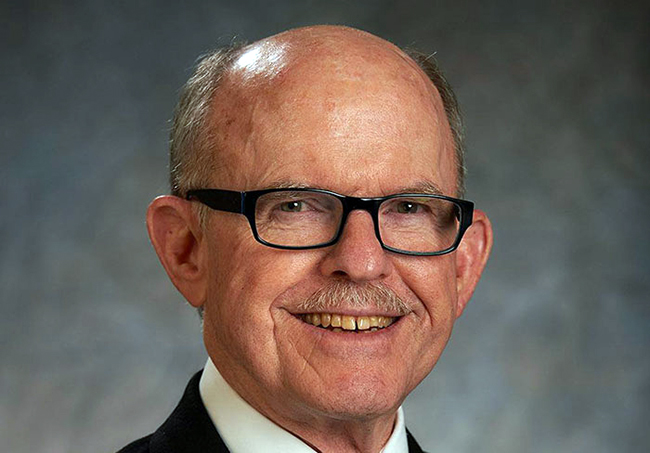

Char Miller, seen in the front yard of his home, is the W.M Keck professor of Environmental analysis and history at Pomona College. COURIER photo/Steven Felschundneff

by Mick Rhodes | editor@claremont-courier.com

In his spectacular new book, “Natural Consequences: Intimate Essays for a Planet in Peril,” Char Miller explores our relationship with a changing climate here in Claremont, providing a fascinating backstory to a crisis unfolding in real time.

Among its six chapters of essays are thoughtful observations, historic explorations, criticism, and solutions to the city’s and state’s ever-increasing extremes in heat, flood, fire, and drought.

Miller is the W.M. Keck Professor of Environmental Analysis and History at Pomona College, where’s he’s taught for 15 years, and the author of more than 15 books and 40 essays. He has a particularly elegant take on Claremont’s historic and recent water woes, from flood to drought.

Miller’s overarching message is simple: keep it local. And for him, that means Claremont.

“Do the work where you live, because that’s where you live and that’s what you know,” he said. “But it means you have to know the place, and that’s largely what this book is about, is how I have come to know Claremont.”

For nearly 100 years, Los Angeles County has imported its water, largely from the Colorado River. But climate change and a century of diversion has reduced that waterway to historic low levels, like many others across the Western U.S. And as supplies recede, the price of importing the increasingly scarce resource goes up.

Claremont residents needn’t be reminded of this certainty of supply and demand. Here Golden State Water Company controls the flow into swimming pools, out of faucets and sprinklers, and it enjoys the considerable spoils.

All that could change, Miller says.

“Now we have to think about the economic costs of maintaining systems that move water hundreds of miles from their source to where it’s going to be consumed.”

At the time the L.A. Aqueduct was being developed in the early part of the 20th century — with the intent of channeling water from the eastern slopes of the Sierra Nevada to the city and the surrounding region — Claremont made a decision: through the guise of the Pomona Valley Protective Association, the city instead endeavored to maintain the natural alluvial fan that wrapped around San Antonio Canyon.

“So L.A. went to get imported water, and Claremont and the Chino Basin Water Conservation District, as it’s now known, to our immediate east, started working on this effort to use the natural system to benefit that system and us,” Miller told the COURIER.

The idea was not new; as hydrology engineers, other experts, and everyday farmers were well aware, when water flowed through the alluvial fan, it would percolate into the aquifer below.

“This is really innovative work in the early part of the 20th century,” Miller said. “And it’s that locally conceived response that I would love us to both recognize — because it happened — but also to model many of our own works on.”

Unfortunately, Claremont’s forward thinking didn’t last. Like the rest of Los Angeles County, the trajectory of its water policy was forever altered as a result of the devastating 1938 flood, which inundated portions of Claremont and much of Southern California with 30,000 cubic feet per second of water rushing out of San Antonio Canyon.

Intent on preventing a recurrence, over the ensuing years federal, state and local agencies constructed multiple dams — including San Antonio Dam north of Upland, completed in 1956, and Prado Dam in Chino Hills, which opened in 1941 — and turned the ancient L.A. River into a concrete channel.

As one might expect, housing was constructed on many of the alluvial fans, which had heretofore provided plentiful local groundwater for generations. All that concrete choked the natural aquifers underneath. Compounding the damage, new agricultural interests also set up shop and employed pesticides and other chemicals that, over time, leeched into groundwater. And, well, here we are.

To be clear, Miller isn’t advocating for the removal of San Antonio Dam.

“The larger point is that we have changed the cycle and made it much more difficult to percolate water into the aquifers beneath our feet,” he said. “So we’ve got to get smarter about how we can infiltrate water back into those systems so that in fact, they serve as underground reservoirs for us. It’s a lot cheaper than building a reservoir.”

In a rare instance of good news about Claremont’s water, the Pomona Valley Protective Association is still at it. The 112-year-old nonprofit, which maintains an office in Claremont, continues to capture and percolate rainwater in order to replenish the region’s aquifers. “Through the capture and spreading of storm water, we replenish the area’s aquifers and release water when rainfall creates groundwater levels that become too high,” according to its website.

Miller envisions a multi-pronged approach to changing our relationship with water, how we harvest it, and from where. It involves conservation on all fronts: eliminating water-hungry lawns in favor of naturally drought tolerant native plants; capturing runoff; utilizing low-flow technology; building more spreading grounds to replenish aquifers; and constructing water treatment plants to clean water extracted from aquifers that have been poisoned through agricultural means by a century of pesticides and other chemicals; and many other efforts.

Perhaps his most ambitious plan is to restock subterranean aquifers where the urban has overlaid the previously rural. Part of this would be convincing public and private entities to create more “bioswales,” which divert and collect storm water runoff and allow it to percolate down into the underlying aquifer, rather than storm drains. Pomona College has several.

Corporate America’s reason for being is profit. Yes, it ‘twas ever thus, but when something as empirically sound as climate change becomes a political cudgel, perhaps we must recognize our societal zeitgeist has reached new heights of arrogance. In this environment, is it even possible to sway government and private water enterprise toward altruism?

“That’s part of the problem, of course, but that’s why I’m such a big fan of incentives: make it possible for big [agriculture] to make the move to more sustainable water management,” Miller said. “So, if the dilemma for them is cash, then let’s get them the money to make the transition,” Miller said. “I’m totally fine with that, because [agriculture] consumes 80 percent of the water” in California. “If we could cut that back to 60 to 50 percent, all of a sudden the game changes, and the droughts that we imagine and experience are less severe at one level. That’s a big win-win for them and it’s a big win-win for us.”

It may mean farmers grow different crops, and rethink products such as almonds, which require massive amounts of water and are primarily exported, Miller said.

“And I don’t mean that other people in the world shouldn’t eat almonds,” he said, “but why should they eat our water? Because that’s effectively what we’re doing.”

California real estate is among the most costly in the nation. Building treatment plants and spreading grounds, not to mention new equipment and training for farmers, would require billions in government investment. Assuming lawmakers are on board, where would the money come from?

California’s “rainy-day fund is billions of dollars,” Miller said, referencing the state’s $20.9 billion in Proposition 2 Budget Stabilization Act funds currently on the books. “Well, let’s start giving out seed money for [agriculture] to help them make the transition in the same way that L.A. County has helped L.A. County make the transition by requiring, through codes, the implementation of low-flow technologies in new household construction,” Miller said.

Getting lawmakers on board with the long-term vision required — because the fruit from the labor of percolating water into aquifers takes decades to present itself — is also a daunting proposition. Even with these encumbrances, Miller believes the future must be in innovation and the familiar “three Rs” — reduce, reuse, recycle — and not in water importation.

“And that’s why I really love the dairy farmers, the citrus growers, and the civic leaders back in the early part of the 20th century,” he said. “They knew they were doing something for themselves to be sure, but that if you filled these alluvial fanned aquifers with water, and managed that process with a sense of stewardship, their grandchildren would benefit from this process.

“I love that sort of pay it forward notion that comes coupled with a kind of more responsibility to those that we actually bring into this world, that we’re not going to leave it in a worse shape than we received.”

Miller said he feels blessed to have grown up in a post-WWII America, where he reaped the benefits of sacrifices made two generations earlier.

“And I want to be able to make the same set of arguments for my grandkids, and for everybody’s grandkids, whoever that inherits this work after we’re gone.”

“Natural Consequences: Intimate Essays for a Planet in Peril” is out now on Reverberations Books.

0 Comments