In mother’s name: longtime registrar leaves $1 million to Pomona College

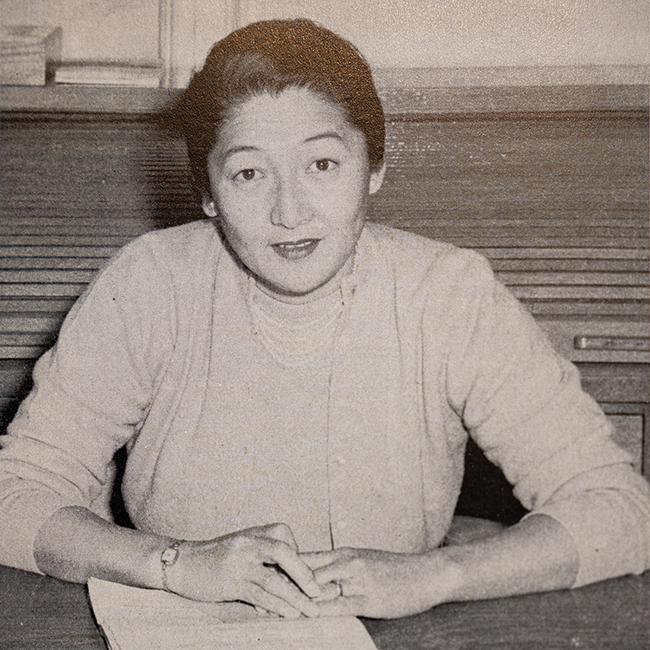

Masago Armstrong, seen here in Pomona College’s 1959 yearbook, was the school’s registrar for 30 years and recently left a posthumous $1 million gift to the university. Photo/courtesy of Pomona College

By Lisa Butterworth

Every student who attended Pomona College between 1955 and 1985 knew the diligence and kindness of Masago Armstrong, who was the university’s registrar for 30 years and died last year at the age of 102. But what they couldn’t have known was her legacy of shaping and supporting students would one day continue — 38 years after her retirement — thanks to a recent $1 million dollar scholarship gift she has left for the university.

The endowment came as a surprise. “Oh my gosh, I was totally blown away,” said Pomona College President G. Gabrielle Starr. “It was just an incredible gift in the true sense of the word.”

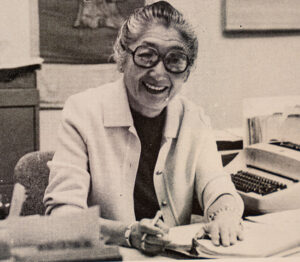

Masago Armstrong in Pomona College’s 1979 yearbook. Photo/courtesy of Pomona College

The gift is certainly aligned with Armstrong’s ethos, however, and the work she had done at the school many years prior. A registrar is essentially a school’s primary record keeper, keeping track of students’ coursework, grades, and credits. Often they are considered staff members, but the role is slightly different at Pomona College. “One of the things that’s unique about our registrars is that they are faculty members,” said Starr. “They don’t teach, but they are voting faculty members, they’re appointed, and there’s a tradition that Masago Armstrong embodied — of having the kind of care and one-on-one relationship that a teacher has with their students.”

Armstrong was born in Menlo Park, California, after her parents immigrated to the U.S. from Japan in 1904 (it’s said that her father Ryohitsu arrived with just $60 and a basket of clothes). That’s where she and her five siblings worked on the family’s thriving flower farm. Her parents prioritized education, and Armstrong graduated from Stanford with a master’s degree in 1941.

A year later their lives were forever changed when President Roosevelt’s executive order forced the family’s internment, first at Santa Anita Racetrack in Arcadia, then four years at Heart Mountain in Wyoming, where her mother Towa died at 51.

Armstrong’s gift to Pomona College is in Towa’s honor.

“She started this scholarship for her mother,” Starr said. “It’s really a story of folks coming to the U.S. in a world that was completely falling apart at the seams. And then [Masago] was sent to a government internment camp. But even with that destabilization, and I’m sure what had to feel at some level like a betrayal, she didn’t give up hope for the future, and this idea that you could make yourself who you wanted and needed to become. This gift is a commitment to making sure that students can access the possibility, the doors that are opened by a college education.”

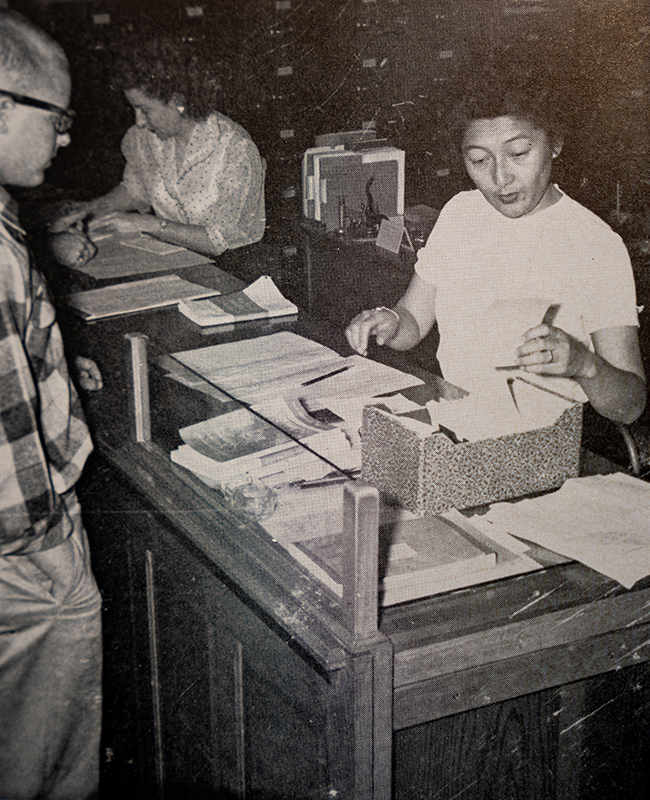

Masago Armstrong is seen here in Pomona College’s 1957 yearbook. Photo/courtesy of Pomona College

Armstrong joined Pomona College in 1955 when E. Wilson Lyon was the school’s president. Lyon had come to Claremont from Mississippi, and though, like Armstrong, he was beloved for many things, Starr relayed one particularly relevant story that took place during World War II. “When it became clear that California and the U.S. were going to intern people of Japanese ancestry, we had two students who were of Japanese descent at the college,” Starr said. “[Lyon] reached out to the president of Oberlin [College] and said, ‘I need to get these students out of here.’” Lyon proceeded to assemble a brass band and then organized a parade down to the train station, clandestinely transporting the two Japanese students in the middle of the musicians. “The brass band was cover, and he got those two students on the train to Oberlin, where they finished their education. So, it is my guess that when Masago came here, she came to an institution that had made its commitment to justice abundantly clear.”

It was a commitment Armstrong upheld. During her tenure as registrar, she shepherded 8,752 students on their journey to graduation. One of those students was civil rights activist Myrlie Evers-Williams, who moved her three children from Jackson, Mississippi, to Claremont to attend Pomona College in 1964, just a year after her husband, civil rights leader Medgar Evers, had been murdered. Armstrong was a beacon of support for Evers-Williams, as she navigated a completely new life in a mostly white community. “[Armstrong] and others were so powerful. So powerful in their excellence, making me think about what I wanted to do,” Evers-Williams told “Pomona College Magazine” back in 2013. “It’s a story,” Starr said, “that comes around in this beautiful circle that makes me so proud.”

As registrar, Armstrong knew which students were excelling, which ones were in need of academic support, and which ones simply needed help, Starr said. She recalled a story from another alum, who had come to Pomona College from Iran. “He walked into the registrar’s office in the late ’70s when the Shah was deposed. And he was terrified he was going to have to go home. It was Masago Armstrong who worked with financial aid and made sure he could stay. She was just part of their lives in this extraordinary way.”

Some students, including the former chair of the Pomona College Board of Trustees, even have physical mementos of their relationship with Armstrong — their school transcripts, which Armstrong meticulously handwrote, even after computer printouts had become the norm. “She did her work out of love,” Starr said, “and she was loved back.”

0 Comments