CGU prof, alum working to help vets’ mental health

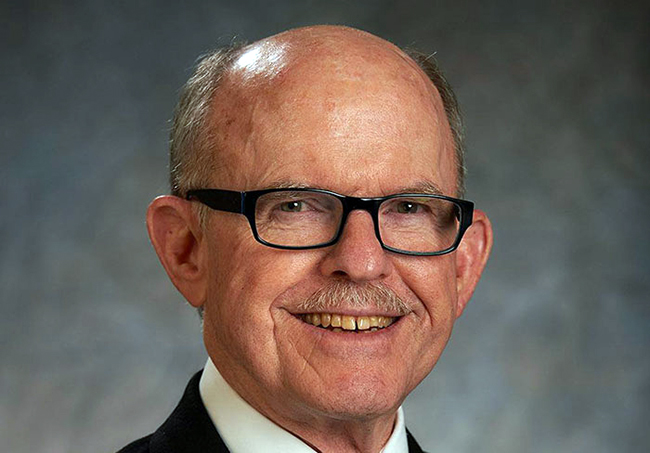

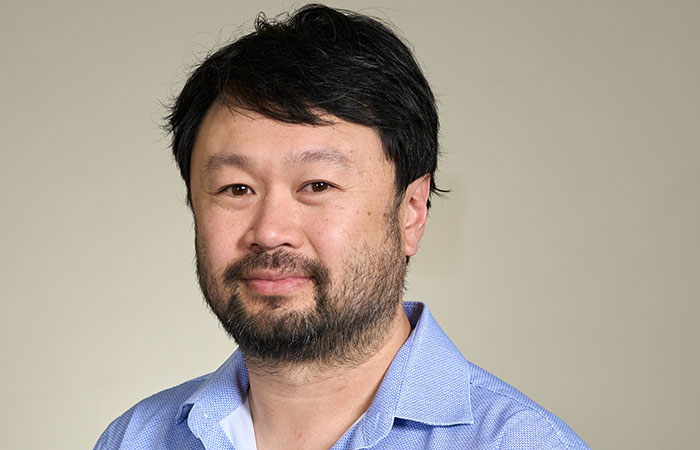

Claremont Graduate University psychology professor Jason Siegel (left) and Leidos/Naval Health Research Center scientist Karen Tannenbaum (right) are collaborating on a federally funded research project aimed at helping military personnel deal with mental health challenges. Photos/courtesy of CGU and Karen Tannenbaum

By Tim Lynch | Special to the Courier

Military personnel pride themselves on being rugged and resilient, but even they aren’t immune to mental health challenges.

Psychology Professor Jason Siegel and recent PhD recipient and Leidos/Naval Health Research Center scientist Karen Tanenbaum are collaborating on a federally funded research project that they hope offers solutions. The goal is to increase help-seeking among early career military members with depression, to reduce self-stigma and public stigma about seeking help, and to increase the willingness of fellow service members to provide social support.

“Military personnel may be particularly unwilling to reveal or report information about their mental health concerns or seek treatment as a function of help-seeking stigma and apprehension about potential adverse impacts on their military career,” Siegel said. “Some people do not realize how hard it is for someone experiencing depression to seek help.”

The research will leverage existing, evidence-based strategies that Siegel and others have used in previous studies. One of the perhaps counterintuitive findings was that messages that directly encouraged people with depression to seek help often had the opposite effect, increasing the likelihood of negative outcomes.

“The same mindset that negatively biases information processing of people experiencing depression also negatively biases thoughts about help-seeking and messages advocating that people do so,” Siegel said. “As such, there are few populations more difficult to persuade than individuals who are experiencing depression.”

Siegel and Tanenbaum will develop and test a help-seeking behavior training that will, for the first time, combine two techniques employed in previous studies: self-distancing and mistargeted communication. In layman’s terms, self-distancing asks a participant to perceive the issue of depression through the eyes of a neutral third party. Another approach asks participants to think of their future self as a source of advice. In previous studies, both approaches achieved better results than directly encouraging someone to seek help.

Mistargeted communication refers to messaging that appears to be aimed at someone else. “It is widely believed that a communication, if inadvertently overheard, is more likely to be effective in changing the opinion of the listener than if it had been deliberately addressed to him,” professors Elaine Walster and Leon Festinger theorized in 1962. Siegel and colleagues conducted similar experiments in 2015 and found that the approach increased help-seeking intentions among people experiencing depression.

“This project gives us an extraordinary opportunity to help individuals who sacrifice themselves for our country,” Siegel said. “Moreover, if successful, we will be able to bring the program to the general population. The idea that our research will be able to help others is why we do what we do. We are fortunate to have this opportunity.”

0 Comments