It’s complicated: CUSD’s careful embrace of artificial intelligence

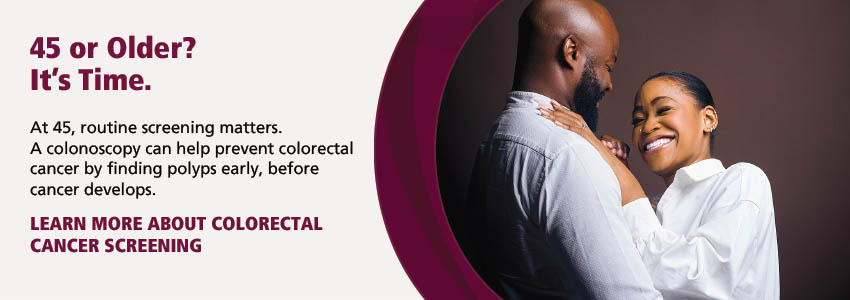

Kara Evans, Claremont Unified School District's director of educational technology and innovation, assists an El Roble Intermediate School student in January. Evans is driving the district’s policy and practical integration and implementation of artificial intelligence. Photo/courtesy of CUSD

by Lisa Butterworth

Artificial intelligence, or AI — and talk of it — is everywhere lately. It’s powering Google searches and customer service chatbots. It’s sorting resumes and interviewing job candidates. AI-generated content is flooding social media, and people are using AI language models like ChatGPT for everything from travel recommendations to therapy. It’s in the news every day.

And, increasingly, it’s in our schools. In a rapidly shifting technology landscape, AI’s role in education presents a new frontier, one that Kara Evans, Claremont Unified School District’s director of educational technology and innovation, said is being thoughtfully considered and intentionally explored.

“We think of ourselves as an innovative district,” Evans said. “It’s in our core values.” Thinking about AI and its implications is one of Evans’ many responsibilities. “We’re trying to be really careful about not jumping too quickly, but continuing to move forward.”

While CUSD might not be ahead of the curve in terms of utilizing AI, Evans said, “We’re not behind.” Some school districts, she said, “aren’t ready to talk about this.” Others are “in a wait-and-see mode.” Still others have come down hard with AI bans at school, only to reverse course when such policies created issues of inequitable access, as New York City’s public schools did in 2023.

Claremont is taking a more innovative approach to AI integration, one that’s grounded in equity and aims to stoke curiosity, Evans said. It stems from the district’s approach to technology in general. “We have a pretty robust professional development program in our department,” said Evans, who was an English teacher at CHS and a teacher on special assignment in educational technology before taking on her current role. “Every teacher that comes to the district gets trained in how to integrate technology in the classroom.”

In addition to six days of training, every teacher gets “one-on-one” time with an assigned coach who models, observes, and provides feedback, helping teachers develop curriculum and lessons. Tech training doesn’t end there. Each year, teachers receive training specific to their grade level — “Here are some new ideas for first grade. Here are some new ideas for history,” said Evans. “Half of it is tech, half of it is collaboration.”

Evans meets with the team that oversees this program for two hours every week, brainstorming about professional development in technology, which, of course, includes AI. “They’ve been part of an AI leadership cohort this year,” Evans said, “so they’re getting a lot of ideas about AI that they’re bringing to those meetings and saying, ‘Hey, why don’t we try this? Why don’t we roll out Brisk to this group?’ Or ‘Why don’t we try School AI just at the middle school?’”

Brisk and SchoolAI are two kid-friendly ChatGPT-like AI tools that Claremont teachers have been experimenting with. Because Claremont includes Apple Distinguished Schools — schools deemed by the tech company to be leaders in education innovation — the tech giant provides the district with an “educational leadership partner,” who shares trends and developments. That’s how the district began testing Rally Reader, an AI-powered app that allows second- to sixth-grade students to pull up a book, read it aloud to their iPad, and get real-time feedback on their pronunciation and fluency.

Though Evans and her team have a great deal of influence, strategies around AI integration and decisions about which AI tools to implement aren’t made in a vacuum. Evans’ department rolled out internal AI best practice guidelines this year, which each school in the district can look to as it crafts its own AI strategies. (A CUSD Board of Education approved policy hasn’t yet been implemented because “[the technology] is moving so fast,” Evans said.)

Next year, the department will create an AI task force of mostly teachers and several administrators, led by teachers on special assignment. “Shared decision making is really a value in this district,” Evans said. “It’s not going to be done in a room of administrators; this is going to be a collective decision about how we move forward.”

The task force will focus on creating a more official policy, shaped in no small part by the legal implications of AI in schools, of which there are many. “One of the biggest legal issues is student privacy,” Evans said. If an AI tool collects and analyzes data, the district must ensure the tool complies with student privacy laws and that the data is properly handled. Other hazards in this minefield include plagiarism and copyright infringement when students utilize AI, as well as fairness and transparency when it’s used by the school. “If an AI tool makes a big decision — like flagging a student for cheating or influencing a grade — that student has a right to know how the decision was made and challenge it,” said Evans.

Another major concern about using AI, is the risk of hidden bias. Evans gave an example: At a meeting, when the leader asked participants to prompt AI to create an image of a yoga instructor, “every single one of us got a young, blonde, white woman,” she said. “We were all using different tools, but we all got similar, very biased results.” Though she repeated the experiment recently with much more diverse results, AI’s unreliability is another concern. “I still think there is a tendency for AI to generate responses that reflect existing social and cultural biases,” she said, “and when students interpret those responses as objective truth, it can reinforce harmful misconceptions.”

While many parental concerns center on how AI is used in school, educators raise flags about how it’s used outside the classroom. A January survey by the Pew Research Center showed that 26 percent of students aged 13 to 17 use AI for help with school assignments (a number that’s doubled since 2023). In the same survey, 54 percent considered it acceptable to use AI for research, while 18 percent found it acceptable to write an essay. Collective anecdotal opinions make those numbers seem much higher, but either way, they’re only going to go up.

It’s an issue Evans hopes forward-thinking about AI will help alleviate. “Laguna [Beach Unified School District] did a survey of students and teachers, and the results were the worst of all worlds, where teachers were feeling like they had to police [AI use], and students were feeling guilty for using it,” Evans said. “What you really want is a world where everybody’s willing to try it and try and figure out how to still make it your authentic work.”

That is the crux of the AI task force’s directive: to understand how AI can be implemented as a tool, rather than a crutch. Many Claremont students are already doing this on their own. Evans recounts a meeting she had with the CUSDSuperintendent’s High School Advisory Council, 11th and 12th graders from Claremont’s two high schools, to talk about AI.

“Every kid in the room was like, ‘Yeah, I’m totally using it.’ And they were using it in amazing ways,” she said. One student had AI create an AP test study guide. Another was having difficulty processing a math lesson, and used AI to create a tutorial to help them understand the concept. “They’re using it in ways that are not just like, ‘Give me the answer,’” Evans said. “I think that’s the key; we want kids to be curious. So we need to design assignments that allow them to be curious, where solving the problem and figuring out how to solve the problem is the most important part, not necessarily the answer.”

AI can be useful for teachers and administrators as well, beyond Turnitin, an AI-detection tool used by Claremont’s high school teachers. Educators can use Brisk to make assignments and activities more inclusive, leaning on AI to help them address students’ particular issues or disabilities. “There are some accommodation kinds of things that it’s just fantastic for,” Evans said.

She also demonstrated an AI tool the district will be using next year, by showing a video of CUSD Superintendent Jim Elsasser delivering a holiday message from his desk in utterly realistic Arabic, just one of 182 languages available. “It’s his voice,” she said, as Elsasser’s facial movements matched the words perfectly. “Imagine if you’re a family that speaks Arabic or Mandarin or Spanish, and the superintendent is delivering a message in the language that you understand best. I think AI can be transformative in those kinds of ways.”

Evans understands there are concerns about the use of technology in the classroom in general, in addition to AI integration. The goal, she said, is “really directional, thoughtful ways of using technology, more dynamic, less passive.” And as her department navigates technology’s role in education, she has made CUSD parents a part of the process as well.

Evans presented the department’s AI guidelines to the district’s equity advisory council, comprising district staff, parents, and community members. “There’s a lot of political heat around AI for a lot of reasons,” Evans said. “I really wanted to talk to those parents about where we are and make sure to just take some time to listen to their concerns.” Wider parental feedback will likely be incorporated into the department’s parent technology series offered in the fall.

As tricky and fast-moving as these AI waters seem to be, Evans is optimistic about the ways CUSD can integrate AI into the curriculum. “But it’s not blind, right? We’re not going into it like, ‘Oh my gosh, we’re in a whole new world. It’s like daisies and sunshine,’” Evans said. “[As an English teacher] I taught ‘Frankenstein,’ and when I did that, I showed a piece of the movie ‘iRobot,’ and that is in the back of my head all the time: wait a second, when do we lose control? So I understand public skepticism or fear of AI. But I also think to say, ‘We’re not going to address it’ is irresponsible. So we’re moving forward. I wouldn’t say cautiously, that’s the wrong word. Carefully; making sure we understand where we want to go, and seeing that strategically before we jump in.”

0 Comments