Mercy and magic at Claremont Manor

by Mick Rhodes | editor@claremont-courier.com

The caregiver at Claremont Manor, aptly named “Mercy,” was back for what would be her final check up on my 84-year-old father-in-law Glyn at about 9 p.m. Tuesday. “Yes,” was all she said, after seeing that his breathing had become very shallow, his gasps for air inconsistent and further apart. It was time.

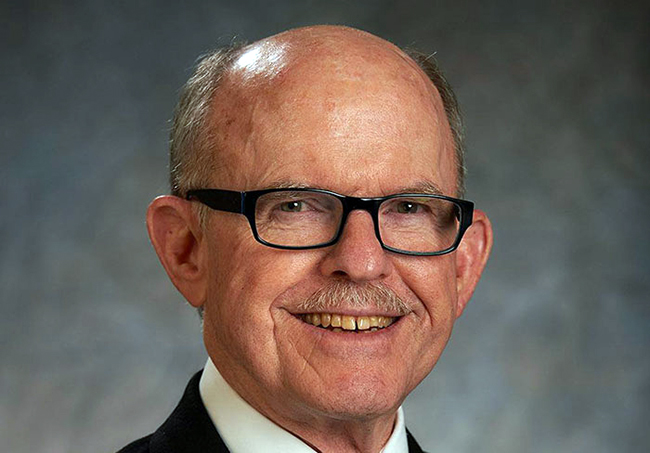

His wife of 64 years, Alison, daughter (and my wife) Lisa, son Warren and his wife Leslie were there, as they had been since Saturday, when his nurse told them to gather the family. Glyn had held on, unresponsive but fighting to breathe, for three more days.

The room was hushed when he finally let go about 10:15. Then it wasn’t. Lisa, who’d been holding her father’s hand since Saturday, and who I’d seen cry only twice in 10 years, loosed decades of grief and worry.

Glyn had suffered with Parkinson’s disease for more than 20 years, and his last couple were bad.

Lisa kept on holding his hand, stroking his face, her hard sobs the only sound. The hospice nurse came in to confirm it all and make it official. It could be three hours or more until Todd Memorial arrives, she said.

So we sat with Glyn. I tried to comfort Lisa. There was nothing left to say or do.

The man from Todd showed up about 12:30 a.m. Wednesday, looking like a character out of a movie in a black suit, black tie, white shirt, black shoes, and black fedora. I thought I was dreaming for a second there, it was so surreal. He did his thing, respectfully and with care. After a few minutes he announced, “With your permission, I will cover his face now.” Glyn’s family got one last look and said goodbye.

They’ll live with memories and photographs now, like we all do when someone dies. That finality is what shakes me most about death; that absence — no more meals, calls, texts, or counsel — is the part that keeps aching and never lets up.

Glyn and Alison met as teens in their native Liverpool, England. They had both grown up amid the terror of World War II, with the German Luftwaffe dropping bombs on their neighborhoods. They married in 1960, and by the time they moved to Africa, where Glyn served in the British Army’s King’s Regiment, they had three young children. In 1981, Glyn’s machinist job then brought the family to the U.S., first to Wisconsin, then to Riverside, and finally — luckily for me — to Claremont about 20 years ago.

In the days leading up to Glyn’s death a procession of family members had made their way from near and far to say goodbye. Though he was unresponsive, I like to think it gave him comfort to hear the voices of his many grandsons, granddaughters, and their partners who came by Monday, filling the smallish, tidy living room with the buzz of youthful energy. Their mild boisterousness helped make the occasion less somber, and best of all it brought joy to Lisa, who had needed something to smile about for weeks.

Over the course of several hours, with all those kids and young folk coming and going, Glyn and Alison’s affectionate, adventurous ginger cat “Rusty” somehow got out. We spent Tuesday searching the grounds at Claremont Manor and asking around to see if anyone had seen him. Leslie posted “lost cat” notices online. It seemed cruel timing with Glyn on the verge of dying that Rusty might be gone as well.

Everyone has their own way of dealing with grief. Some retreat inward. Others busy themselves with anything but their feelings. Life is never the same afterward, regardless. As our loved ones leave us, we’re changed forever. There’s no “getting over it,” no “moving on.” We simply have a new life after their deaths. There’s no forgetting. We find a way to go forward, but the wound remains, part of us, permanent.

And time does what it does, unrelentingly. If we’re truly lucky one day the pain begins to ebb and is slowly replaced by ever more gratitude for the time we had with our person. That’s the best we can hope for.

After the natty undertaker took Glyn away, Alison was without him for the first time in 64 years. I tried to imagine what that might feel like. I couldn’t.

Their kids began doing practical things like disassembling Glyn’s hospital bed — a totem of his suffering they were eager to have out of sight — and moving it into a spare room. The floor was swept, and gadgets unplugged. The living room was returned to the living.

The confusion over what will come next hung in the air, along with the grief.

It was getting late. Alison prepared for her first sleep as a widow. Warren and Leslie readied for home. Lisa stepped out onto the balcony to get some air.

A few seconds later I heard something unbelievable. “Rusty? Rusty! Kitty!” Lisa shrieked. The erstwhile cat had returned, not 30 minutes after Glyn had left.

“Glyn sent him back to me!” Alison said, beaming. “He knew I needed comfort.”

It was beautiful. After all the suffering, something approaching magic had occurred. Maybe Glyn did send Rusty back. I want to believe it’s possible a family in pain could get a love letter from the beyond like that. If not magic, it was at the least a well-deserved lucky break.

Bearing witness to Glyn’s slow-motion Parkinson’s disease decline was rough on everyone concerned. At the end he had a houseful of family affirming their love and admiration for him, holding him close as he journeyed onward. And that’s about as good as it gets.

0 Comments