Reflections on 25 years part I: The Vanguard effect

by Donald Gould

Twenty-five years ago, I started Gould Asset Management in a small office above what was then Goldstein Optometry, on the east side of Indian Hill Boulevard between First and Second streets. The occasion of our silver anniversary prompted me to reflect on the major changes I’ve witnessed in the investment world since 1999. This is the first in a series looking back at major developments over the last quarter century, and lessons learned.

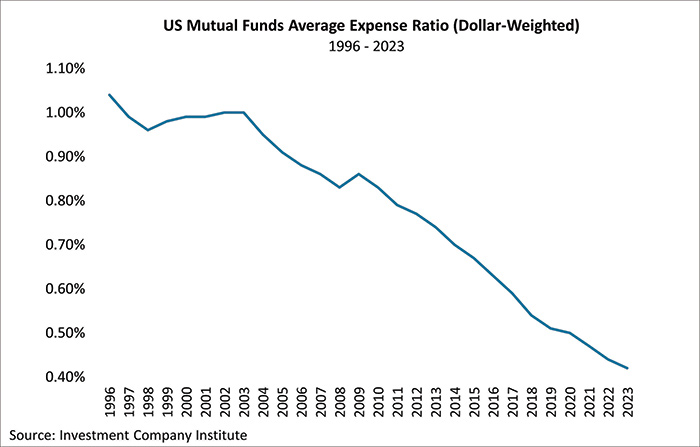

The Vanguard effect: driving down fund costs

Among the most important financial services industry trends of the last quarter century is the steady decline in the cost of core investment products such as mutual funds. It all began with Vanguard, the mutual fund behemoth launched in the 1970s. Unlike for-profit fund companies, Vanguard’s management company is indirectly owned by its customers, the investors in its funds. Consequently, Vanguard charges only enough management fees to cover its costs, with no profit margin added on, leading to lower fund expenses than most competitors.

This cost edge has given Vanguard funds a lasting performance advantage, enabling Vanguard to grow faster than its competitors. As a fund grows, its fixed costs are spread over a larger base, leading to still lower fund expenses per dollar invested, a larger performance advantage, and yet bigger funds — a virtuous circle.

Thanks to Vanguard, price competition has spread across the entire fund industry, bringing down costs for all investors and effectively shifting hundreds of billions of dollars annually from fund managers to investors. Vanguard’s founder, the late Jack Bogle, arguably has done more for investors than anyone else, ever.

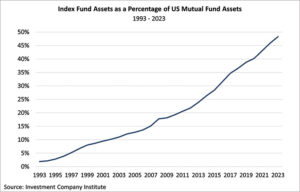

Enter the index fund: investments get commoditized

But the story would not be complete without another Vanguard innovation, the index fund. An index fund simply seeks to replicate the performance of a selected index (such as the S&P 500) by owning all the component stocks of the index in the same proportions as the index.

Index funds have become a commodity — Vanguard’s and Fidelity’s S&P 500 funds are virtually indistinguishable, holding the same stocks in the same proportions. Like soybeans or copper, there is essentially no difference between two index funds following the same index. So, like dueling gas stations on opposite corners, index fund providers must compete on their management fees, which have become vanishingly small. Many index funds charge less than two basis points annually, which equates to under $20 per year on a $100,000 investment.

Historically, mutual funds were promoted with the idea that if you just picked the right fund (which employed the right manager, who picked the right stocks), you would beat the pack. But because the average performance of all investors is, by definition, average, for every stock picker who beats the average, there must be one who trails it. Unlike in mythical Lake Wobegon, all money managers cannot be above average. Compounding the challenge, markets seem to be mostly efficient. That means that a manager who beats the market in one year has only a coin’s toss chance of doing it again the next year.

Collectively, non-index funds, aka active funds, perform in line with an index fund (before expenses and taxes), though individual fund performance varies widely. This is true, even if you could find that elusive manager who consistently beats the market.* When we consider the higher expenses of active funds, their collective performance consistently trails the performance of index funds. So, it’s no surprise that index funds have steadily gained market share in recent decades.

(*For a short and essential read on this topic, see Nobel laureate William F. Sharpe’s “The Arithmetic of Active Management” at web.stanford.edu/~wfsharpe, click “earlier publications”/“online publications.”)

Exchange-traded funds: a better mousetrap

A third innovation is the exchange-traded fund, or ETF. The ETF is a special form of a mutual fund that trades continuously throughout the day, like individual stocks. Traditional mutual funds trade only once a day. First launched by State Street Bank in 1993, the ETF is in many ways a better mousetrap than the traditional mutual fund, offering greater liquidity and ease of trading, better tax efficiency, and lower costs. ETFs, which are mostly index funds, have boomed in recent decades and represent the latest chapter in the commoditization of investment products.

In a commoditized world, the biggest players tend to have the lowest prices. Think Amazon and Walmart in retailing. Their counterparts in the ETF world are BlackRock and Vanguard, which together control about two-thirds of the market. Each firm oversees roughly $9 trillion in assets.

Next up is, Part II — The empire strikes back: investments get complexified.

Don Gould is president and chief investment officer of Gould Asset Management of Claremont.

0 Comments