Stocks continue ascent and the big get bigger

by Donald Gould | Special to the Courier

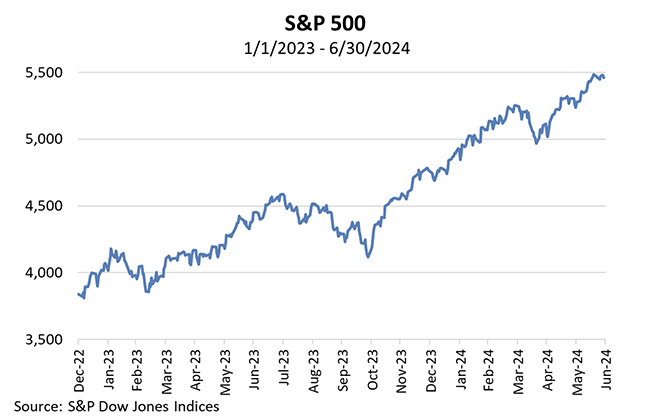

Few expected stocks to repeat their stellar 2023 performance in 2024, but markets are doing just that and at their current rate could even eclipse last year’s run. While the pace of the rise moderated in the second quarter, the leading global stock benchmark added about 3% in the second quarter, taking its year-to-date gain to nearly 12%. Meanwhile, the S&P 500 U.S. large cap index did better still as a handful of tech giants fueled a 4.3% second quarter rise, bringing the year-to-date return to a heady 15.3%. Since the 2022 financial markets debacle, the S&P 500 is up a remarkable 45.6%.

Bond returns have been muted this year, with interest income offset by modest bond price declines due to modestly higher interest rates. But both stocks and bonds may benefit from newfound, if cautious, optimism that the economy will achieve a soft landing, bringing inflation back toward central bank targets without a near-term recession.

Curbing our enthusiasm

To put recent equity market returns in perspective, U.S. stocks have compounded at an average rate of about 10% per year over the past century, so we’ve seen about four years’ worth of normal returns in just the past 18 months. As usual, we have no crystal ball — returns over the next three, six, or 12 months could fall anywhere on the map. But common sense tells us that in an economy growing at its long-term trend rate of about 2% per year (net of inflation), recent equity market returns are not sustainable.

Further tempering the outlook is that by historical measures, U.S. stocks are expensive. What do we mean by “expensive?” We compare how much investors are paying for a dollar of corporate earnings (from stocks) to what they must pay for a dollar of bond interest. As compensation for accepting the much greater volatility of stock markets, we would expect a dollar to buy more earnings than interest. When the spread is narrow, the expected reward for owning stocks is less, and in that situation, we might say stocks are expensive.

By our measure, the S&P 500 is (by a small amount) at its most expensive since at least 1941. Sadly, knowing when stocks are expensive has not been a reliable guide for market timing (and nor has anything else). Stock markets can remain expensive for a long time and continue climbing throughout. And there’s never any guarantee that historical relationships will be the norm in the future. Nonetheless, we believe the risk-reward tradeoff for stocks is less attractive than usual.

The big get bigger

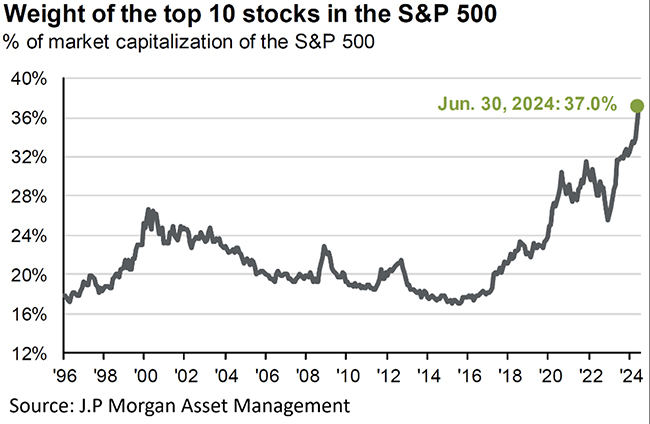

The 10 largest U.S. stocks now account for 37% of the S&P 500’s total value, their highest level since the 1960s. Just three stocks — Microsoft, Nvidia, and Apple — make up 21% of the index value. As investors, should we be concerned about the rising concentration? The answer is a definite maybe.

Those who worry about growing concentration cite similar periods in market history that ended badly. Some recall the so-called “Nifty 50” from the late 1960s. (“nifty” seems so quaint now.) Xerox, GE, IBM, and Coca-Cola headlined the list of companies to buy and hold forever. The problem with this almost religious devotion to any set of stocks is that investors begin to ignore price — almost any stock price can be justified — for a time. Eventually, usually after a negative turn in investor sentiment, people begin to scrutinize how much they are paying for an uncertain stream of future earnings. Before long, this buy-and-hold-no-matter-what wisdom is widely (and smugly) regarded as just another chapter in the long history of foolish speculative manias. Such was the fate of the Nifty 50.

Arguing the other side are those who say that this time is different. Today’s market leaders are viewed as quasi-monopolies that have already won a winner-take-all game. The omnipresence of Microsoft software, Apple iPhones, and Nvidia chips (reportedly an 80+% share of the AI chip market) makes this a compelling argument.

Hedging your bets with index funds

Absent the crystal ball, it’s impossible to know which side will prevail. Fortunately, you don’t need to pick sides. Diversification through index funds assures exposure to the market’s leaders. Index funds are often called “passive” because they simply replicate the weightings of a selected benchmark index such as the S&P 500. In fact, indexes (and the funds that follow them) are quite dynamic. Their company weightings change minute to minute based on the relative performance of the component stocks. Additionally, stocks are regularly added to (and removed from) the index based on such factors as a company’s growth (or shrinkage) and company mergers.

Most importantly, the stocks that perform the best make up a growing share of the index over time. If today’s big keep getting bigger, their weight in the index fund will continue to grow. And just as important, when today’s leaders are ultimately supplanted by companies we’ve not yet heard of, the index fund will own those, too.

Don Gould is president and chief investment officer of Gould Asset Management of Claremont.

0 Comments