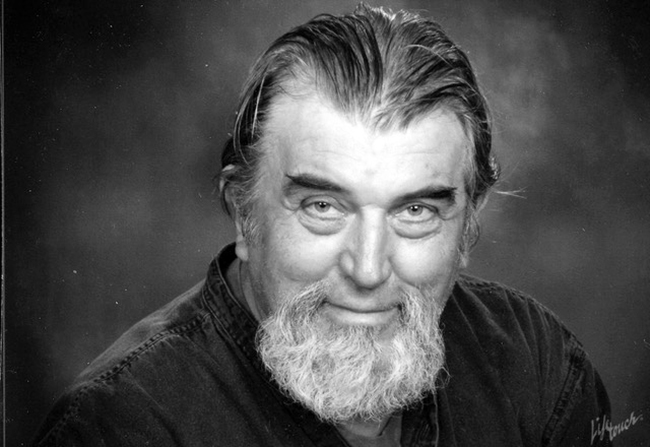

Obituary: Harrison McIntosh

Ceramicist, loving husband, father

Harrison McIntosh, celebrated ceramicist and longtime Claremont resident, died on Thursday, January 21, 2016 in Claremont. He was 101.

Mr. McIntosh was part of southern California’s “revolution in clay,” which in the 1950s elevated ceramics from mere craft to fine art.

Mr. McIntosh made well over 9,000 pieces over the years, drawing inspiration from the Bauhaus movement, Asian pottery and Swedish ce

His long career as a ceramic artist, known for his strong sensual shapes, spanned eight decades and included his modern approach to classical vessel forms in the 1950s to his work in sculptural spheres floating on geometric chrome forms. He is especially known for work enhanced by distinctive surface decoration of thin sgrafitto lines or rhythmic brush spots.

His pots can be found in more than 40 museum collections across the globe, including the Louvre in Paris, the Smithsonian in Washington, DC, the Mingei in Japan, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, the American Museum of Ceramic Art (AMOCA) in Pomona and the Huntington Library, Art Collections and Botanical Gardens.

AMOCA founder David Armstrong called Mr. McIntosh “one of the great gentlemen of ceramics as we know it today” as he reflected on the loss of an artist he admired and a friend he cherished. “Harrison added a great deal of dignity to the profession and will be truly missed by all who loved him,” he said.

Mr. McIntosh was born in Vallejo, California on September 11, 1914 to Harrison and Jesusita Coronado McIntosh and raised in Stockton. Early on, he and his younger brother Robert became interested in drawing and painting. They were mentored by Arthur Haddock, a local landscape artist, and Harry Noyes Pratt, director of the Haggin Museum. The latter advised the boys to trade Stockton for a larger city with more opportunities.

When Robert accepted a scholarship to the Art Center College (now Art Center College of Design in Pasadena) in 1937, the whole family moved with him to Los Angeles. Harrison got a job at an art supply store where he made frames, honing his skills in carving and molding. It is here that he met Millard Sheets at the nearby Institute of Western Art. He found his true vocation after visiting the 1939 San Francisco World’s Fair, where he was inspired by the Japanese ceramics and folk art pavilion.

At young Harrison’s urging, the renowned architect Richard Neutra had been commissioned to build the family home. He made sure plans included a home studio. The first work Mr. McIntosh created there was a two-foot-high clay torso he had fired at a local terra cotta company. This and other works were showcased during his debut exhibition at the Bullock’s Wilshire department store in Los Angeles

In 1940, Mr. McIntosh began taking night classes at USC, studying under influential ceramicist Glen Lukens. His studies were put on hold in 1944 when he was drafted into the US Army where he served as a medic. He was released early when his first wife, whom he married in 1942, became ill and died.

When he discovered he could use the GI Bill to continue his ceramics studies, Mr. McIntosh headed for Claremont Graduate School where, from 1949 to 1952, he studied as a special student with Richard Petterson on the Scripps College campus. It was then that Harrison first began producing wheel-thrown pieces, which were featured in local exhibitions. Before long, he set up a studio—in a stone building across the street from Wolfe’s Market on Foothill Boulevard in Claremont—which he shared with fellow ceramicist Rupert Deese.

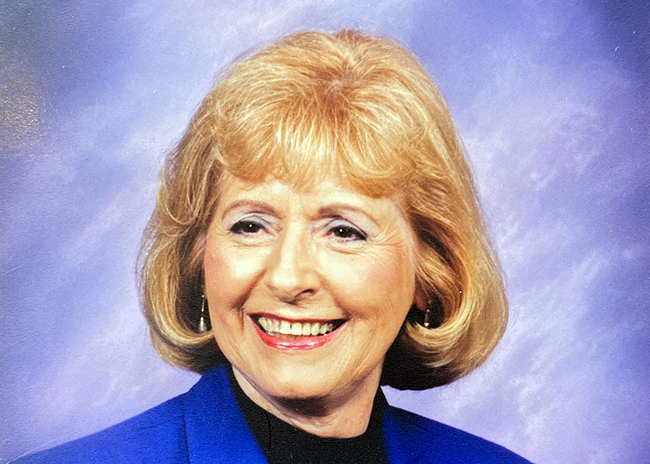

Mr. McIntosh found more than artistic mentorship at the Claremont Colleges. He found love as well when he met Marguerite Loyau, a fellow student and Fulbright scholar who came to Claremont from France. They had a lot in common. They were both trained in the fine arts and found inspiration in nature, animals, people, beauty and love. They also shared the same taste and interests in politics, art, literature, music and even religion.

They were married in 1952, the first couple to wed in the newly-built Our Lady of the Assumption Church in Claremont. They welcomed a daughter, Catherine, two years later. In 1958, the McIntoshes built a home in Padua Hills, complete with a joint studio for Mr. McIntosh and Mr. Deese. The two friends, both known for their quiet and friendly natures, would work side-by-side for more than 50 years.

“It’s funny that in my youth it didn’t seem at all strange to me that two artists would have such a long and close working relationship,” Mr. Deese’s daughter Mary Brow said. “That was our ‘normal,’ I guess. It’s really only with the passing of time and with more life experience that I have come to appreciate what a rare partnership they had.”

Mr. McIntosh dabbled in professorship in the summer of 1959 when he was hired by Millard Sheets to teach at the Otis Art Institute as a substitute for Peter Voulkos. He soon realized that he wanted to make art rather than teach it. And that’s just what he did, turning out piece after piece until, by 1980, he had become internationally acclaimed.

In his earlier years, he sold his work at stores like Bullocks Wilshire, Van Kepple Green in Beverly Hills and Abacus in Pasadena. He designed prototypes for Metlox pottery and tiles for Interpace and in the ‘70s traveled with Marguerite to Japan and Germany, where they designed dinnerware and glassware for Mikasa. In the ‘80s and ‘90s, his work was represented first by Louis Newman and later by the Frank Lloyd Gallery.

Mr. McIntosh felt a great sense of comradery with the other pioneering artists of Claremont. He met weekly at Walter’s Restaurant with Mr. Deese, woodcarver and furniture maker Sam Maloof and painter James Heuter, who were collectively called “The Four Friends.” Painters Karl Benjamin and illustrator Paul Darrow often joined them.

“When I look at [photos of the group], I think about my own friends creating music, film and art together today and how those works will someday shape the world,” Mr. McIntosh’s grandson Jack Tuggle said. “I think about my grandpa’s life as a lesson in how a community can drive artists to greater heights and how great art is a reflection of that community.”

By 2006, his vision loss had forced Mr. McIntosh’s retirement, but he continued to enjoy an adulation springing from his ceaseless dedication to ceramic art. In the fall of 2014, AMOCA marked his centennial birthday with an exhibition titled “HM100: A Century Through the Life of Harrison McIntosh.”

More than 500 people attended the reception to wish Mr. McIntosh well and take in his hundred most influential pieces. “As he turned 100, he reached a state of completeness and happiness,” his wife Marguerite shared. “He always had a state of spiritual equilibrium that you could feel in his work.”

Gayle Blough, wife of the late John Blough, another noted Claremont ceramicist, expressed regret upon hearing of Mr. McIntosh’s death. “There is something special, sensual and loving about potters; and now we’ve lost another great one,” she said.

He is survived by his wife Marguerite, daughter Catherine McIntosh, son-in-law Charles Tuggle and grandsons Jack and Sam Tuggle.

A funeral mass will be held on Friday, February 19 at 2 p.m. at Our Lady of Assumption Church, 435 N. Berkeley Ave. in Claremont, followed by a reception at Mt. San Antonio Gardens.

A Celebration of Life is planned for 3:30 p.m. on Sunday, February 28 at Garrison Theater. The family has requested that donations in Harrison McIntosh’s memory be made to the American Museum of Ceramic Art, the Claremont Museum of Art or Our Lady of Assumption Church.

0 Comments