Sins of the father: a complicated legacy

by Mick Rhodes | editor@claremont-courier.com

It was difficult to comprehend what I was seeing in that Lake Tahoe hotel room back in 1993. We’d had a few beers and shared a joint, and things were a little fuzzy.

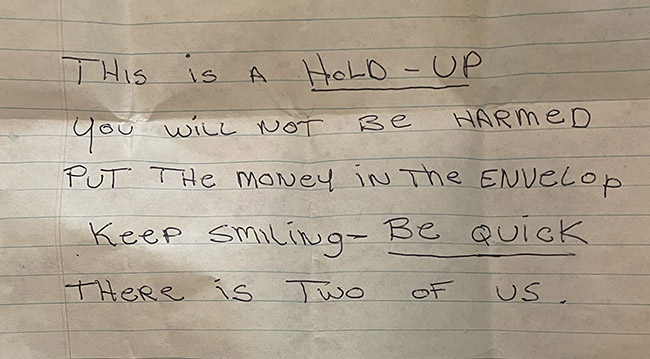

“This is a hold-up,” read the note, handwritten on neatly folded yellow legal paper. “You will not be harmed … Put the money in the envelop … Keep smiling – be quick … There is two of us.”

It was a bluff, he told me. He worked alone and never used a gun, but always kept one hand in his coat pocket just the same. The note, his stature, and demeanor were enough to get what he came for.

He would hand that note to a bank teller and stand there calmly while she — it was always a woman, he said — crammed stacks of bills into a manila envelope. That kind of risk — and cruelty — was as foreign to me as I could imagine.

I’d never been so close to a criminal before, and this one was my father.

Dad left before I turned 2. It was 1965, four years before California’s landmark Family Law Act, and divorces in the Golden State were still adjudicated under the aegis of the primitive legal architecture of the mid-19th century. No matter. Mom wasn’t interested in child support. She wanted a clean break and she got it: he was gone, and we never heard from him again.

I put up a good front, telling people I didn’t miss growing up with a father because my mom was such a powerhouse. That last bit was true, the first part mostly.

I decided to find him after my kids started being born. It didn’t take long. He was in Covina near his mother — my grandmother — who was also a stranger to me. I’d spent most of my childhood a couple miles up the road in Glendora but never knew they were there.

We met in the fall of 1992. He was 50 and I was 28. It was awkward. But over the coming months we would get together for meals or drinks. I got to know him. We took it slow. It was good for both of us, it seemed.

The next winter he showed up unannounced in North Lake Tahoe, where I was living with my then wife and our 8-year-old daughter. Clearly more animated than I had seen him, he was in the mood to party. So, he and I went down the hill to his hotel room at the Hyatt Incline Village, had a few beers and smoked a joint.

I asked him what he was doing in Tahoe. He cracked a little grin and said he’d been “on a business trip.” It turned out he’d robbed a couple of banks in Southern California and was ostensibly on the lam.

This was, as one might imagine, stunning news.

“Were you scared?” I asked. “Just scared to get caught,” he said. “Nobody wants to get hurt, so as long as I’m smooth and fast, y’know, it’s pretty easy.” I asked about the mechanics. That’s when he showed me the note.

He told me he’d been robbing banks on and off for decades and had spent time in prison for it, as well as for a “misunderstanding” involving a guy who’d wronged him and a baseball bat. I was astounded. The weed and alcohol only amplified the surreality.

Then we went down to the casino and played blackjack and drank too much.

Growing up, mom was always clear: dad was using heroin, she didn’t want to raise me in that environment, so we left. One of the countless emotionally intelligent things she did for me was to never trash talk him. She never said an unkind word. She’d tell me though he was absent, he loved me very much. Yes, it was confusing to hear as a young boy since I’d never had so much as a phone call from him, but in hindsight it was much less traumatizing than it would have been had she chosen to vent her justifiable anger.

I later learned my father came from a long line of rough around the edges old-school Irish alcoholics, some who lived outside the law, and mostly all unable to show love or affection. I’d long ago forgiven him for checking out on fatherhood, but learning he came from an entire clan of emotionally stunted men helped bring a little more focus to the picture.

Mom did what she had to do, and dad did what he knew how to do.

I imagine he rationalized the scars his robberies left on the bank tellers unlucky enough to have seen that note: since nobody was actually hurt, then what’s the harm? His threats, both written and implied, though ultimately empty, were the by-products of a trauma informed life that left him ill-equipped to ponder hifalutin concepts like collateral psychological damage.

Back in Tahoe, dad’s felony-fueled luxury vacation soon came to a close. He threw his small gym bag stuffed with cash — some of it stained blue from exploded dye packs — into his tidy but tired early-1980s Chevy pickup and headed south on the 395.

It wasn’t a month before I got a letter from a federal correctional institution in Safford, Arizona. The feds had searched their database for known bank robbers with his M.O. — including, presumably, the phrasing of his note and its deeply telling, pathos-laden spelling and grammatical errors — and his name popped up. They picked him up without incident at his Covina apartment.

He spent the next four years in prison. We exchanged letters every few months. He wrote mom too, scrawling “I love you” on Valentine’s Day cards.

By the time he was released I’d divorced and was preparing to marry again. He and I took up as if no time had passed. We became close over the ensuing years, spending as much time as we could together, often with mom, completing our unconventional nuclear family.

Dad got work as a framer on a construction crew. He bought a car. He was increasingly fun to be around and seemed to be in a good groove.

It felt like the end of something for me, as if the reunification had healed an unseen wound.

In June 2002 dad fell while getting out of bed and broke his foot. At Inter Community Hospital in Covina they ran his bloodwork and some routine scans. The news was bad: a lifelong smoker, he had advanced lung cancer, and it had spread.

Within days I was shuttling him to and from the VA Hospital in West LA while technicians hit the cancer with radiation. In between oncology appointments we’d sit on a bench in the massive parking lot and he would smoke. We talked about some of the places he’d lived, mostly beach towns up and down the California coast, people he’d known, lovers and friends. It felt good to be there to advocate for him, even though I was horrified, and, if I’m being honest, a little amused that he hadn’t yet quit smoking.

He’d be depleted at the end of the day and I’d drive him home, mostly in silence.

On July 16, 2002 my second daughter Grace was born at St. John’s Hospital in Santa Monica, and I brought dad in to meet her. In the 10 years I had known him I’d never seen him so joyful. He’d bought a pink stuffed bear downstairs in the hospital gift shop, a present for his new granddaughter. She would later name him Freddy.

Two weeks later my phone rang in the early morning hours. Dad had lost consciousness at home, had been taken by ambulance to Inter Community, and died. He was 60.

In the 21 years since he’s missed the birth of two more grandchildren and two great-grandchildren. I’ve had my own health scares, have been divorced and remarried, and mom died in 2017.

Though he was a complicated man, weak in many ways and deeply flawed (who among us isn’t?), I have no regrets about getting to know my father over the 10 years I had with him. We were a family, albeit an odd one.

I hope he felt relief at the end in letting go and living with vulnerability for a while. I like to think his final years were in part a big middle finger to a long line of bastards and outlaws, and that a pattern was broken.

0 Comments