Viewpoint: Trump and name-calling in political discourse

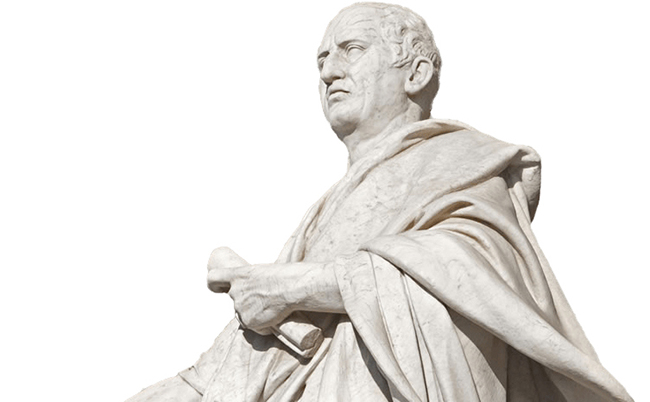

Photo/courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

by Jenny Andersen | Special to the Courier

Media commentators noted a shift in tone at the recent Democratic National Convention in Chicago. Political conventions always douse audiences with waves of political rhetoric, but a new style was detected among Democrats, departing from the turn the other cheek, take the high road philosophy of rhetorical moderation. The Democrats seem to have discovered the power of laughter as a weapon, making witty observations and taking clever jabs at their opponents. Barack Obama, for example, called Donald Trump’s practice of giving nicknames to his political opponents “childish.”

Trump is not the first president or presidential candidate to use political nicknames, but he uses them so often that Wikipedia devotes an entire entry to them. Everyone is by now familiar with “crooked Joe” (for President Biden), “crazy Hillary” or “crooked Hillary” (for Hillary Clinton), but the novelty of facing new opponents (Kamala Harris and Tim Walz) so late in the campaign forced Trump to invent new names on the fly, giving us a chance to see his process of oratorical invention in real time. Democratic strategist David Axelrod describes Trump’s campaign speeches as “improvisational,” observing that he hits upon nicknames by trying out various options with live audiences. In the case of Walz, he quickly settled on (the exceedingly childish) “tampon Tim.” For Harris he has tried out “crazy Kamala,” “laffin’ Kamala,” “lyin’ Kamala Harris,” and “Kamabla.”

In ancient Roman oratory Cicero often used humor (including nicknames) in law court or senate speeches to lighten up the atmosphere. In 70 BCE Cicero was appointed by a special prosecutor on behalf of the citizens of Sicily to prosecute the Roman governor of Sicily in the extortion court. In his Verrine Orations Cicero charges Gaius Verres with theft and manipulation of the legal process on scale so large as to turn Sicily into a criminal state of extortion under his governorship. Despite delaying tactics employed by Verres’s legal counsel, Cicero would go on to win the case. Throughout the trial, Cicero repeatedly played on the name Verres (“verres” in Latin means “pig” or “boar”). The sound of Verres’ name also appears Latin verbs meaning “to sweep or carry off” (“verro” and “everro”), creating further opportunities for clever puns.

Cicero learned Verres’s nickname of “the boar” from Sicilian citizens he interviewed to gather evidence for the trial. Verres preempted retaliation or resistance from his victims by bringing them up on false charges such as spying. Many of Cicero’s Sicilian clients were fleeing trial on such capital charges, having already been flogged or fined. For the brutal legal sentences engineered by Verres, Sicilians pictured Verres as a boar with blood on his snout.

For the priceless collections of bronze statues and other artifacts that he stole, they found the echo of Verres’ name in the verb for “carry off” (“everro”) bitterly appropriate. Cicero quotes the Sicilians’ playful name-calling of Verres a “monstrous hog” (“immanissimum verrum”). The Verrine speeches are peppered with witticisms and joking references to Verres’ crimes while punning on his name. Cicero was conducting a legal prosecution in which he presented mountains of evidence and witnesses to establish Verres’ guilt. The nickname, while humorous, Cicero reminded the court, was not baseless slander or libel, “I should not recall these jokes, which are neither all that funny nor in keeping with the serious dignity of this Court, were it not that I would have you remember how Verres’s offences against morality and justice became at the time the subject of common talk and popular catchwords,” he said.

I do not intend to dignify Trump’s political name-calling by giving it a venerable classical lineage. Far from Trump’s cavalier, libelous (and yes, often childish) name-calling, Cicero had a sense of rhetorical decorum and understood that while playful nicknames could help criticize vices and point out crimes, they also raised a problem of the appropriateness, moderation, and decorum of legal and political speech. A number of respectable news publications have suggested that Trump “talks like a mob boss” or “uses Mafia-inspired language.” The language practices of the Mafia would be much closer in time and geography to Trump than the oratory of Cicero. I leave it to modern linguists to establish that connection.

Claremont resident Jenny Andersen is a professor of English at California State University, San Bernardino.

0 Comments