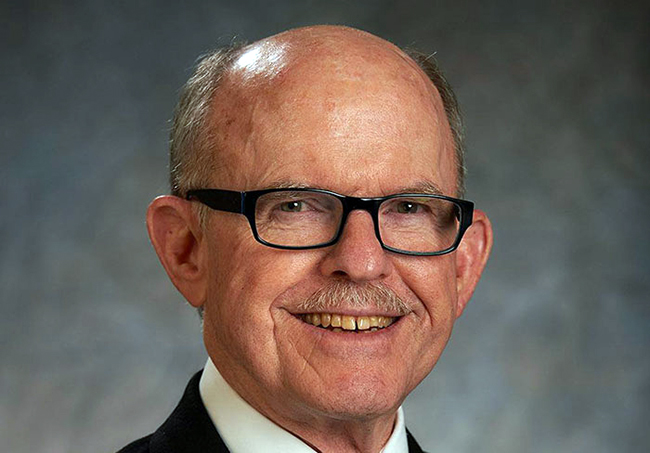

2024 Claremont City Council candidate profile: Corey Calaycay

Incumbent Mayor Pro Tem Corey Calaycay, 54, is aiming to hold onto his Claremont City Council District 1 seat on November 5, when he will be challenged by Rachel Forester. Courier photo/Andrew Alonzo

by Andrew Alonzo | aalonzo@claremont-courier.com

Incumbent Mayor Pro Tem Corey Calaycay, 54, is aiming to hold onto his Claremont City Council District 1 seat on November 5, when he will be challenged by Rachel Forester.

A veteran of Claremont politics, Calaycay has spent five terms in office, starting in March 2005.

“I believe that I have several years of experience. I’m aware of the issues,” Calaycay said. “I have some level of institutional knowledge and memory to bring to the job.”

He has a degree in business administration from Loyola Marymount University, is a Foothill Transit Executive Board member, San Gabriel Valley Mosquito and Vector Control District trustee, a Clean Power Alliance Board member, is Pomona Valley Transit Authority Board chair, and LA County Library Commission chair.

“I think it’s important to have the balance of new blood, [and] at least someone who has some experience and some memory of some of the issues that we’ve dealt with over the years,” Calaycay said. He said he’s not contending “the old ways of doing things are always the right ways of doing things,” only that a balanced perspective is necessary.

Calaycay said one of the biggest issues facing the council causes him constant frustration: “The state superseding our local authority in many cases.”

“Over the years, despite some critics, I believe that we have addressed issues such as housing,” Calaycay said, citing the construction of Courier Place in 2011, the passage of the city’s inclusionary housing ordinance in 2006, and the city exceeding its “housing numbers with regards to moderate housing.” He added he’s helped approve various housing projects in the past meant to hit Claremont’s Regional Housing Needs Allocation and has a record of supporting housing of all types.

“In some respects, we’ve done better than other cities, and yet we were treated as all other cities, that we aren’t doing enough. And so therefore the state feels there’s a need to override our local development authority. I think that’s one of the most important roles that a city has. At the point the state’s taking away all of … those local decisions. I mean what is the point of having a city council anymore.

“The government closest to you is still the best government,” Calaycay said. “Even if sometimes when people don’t always get the answers they want, it’s still a lot easier to engage us here on the local level — just coming down to city hall or running into us at events in town or the supermarket as the case may be. Try that with your county and state officials.”

Though the state may have the final say as to how cities develop housing, “It’s always important for somebody to be questioning this and speaking out,” Calaycay said. He said addressing short-term rental legislation, housing inventory, and development processes are top of mind.

Claremont is tasked with reaching its RHNA of 1,711 new housing units — 556 extremely low-income units, 310 low income, 297 moderate income, and 548 above moderate-income units — by October 2029.

“A lot of these mandates [that] are coming down from the state, they don’t necessarily address the problem,” Calaycay said. “They don’t make people whole, and they can be very, very detrimental to our local government and some of the policies that we’re trying to strike a balance in regards to.”

“The greatest concern I think [is] the program itself is not realistic,” he said. “A big challenge of course with housing is the funding. And even as we’re facing the challenges with the state budget at the moment, there’s limited funding.”

Using permanent supportive housing units as an example, he said even when units are proposed, they’re hardly ever affordable, as conventional construction ranges from $600,000 to $700,000 per unit. He later clarified in an email his use of “‘Affordable’ … is probably better stated as being hardly cost effective or economical relative to limited housing money available for developments. It is affordable to the end users if they aren’t paying for it. However, it is not affordable to the taxpayers, who are not having their tax dollars maximized when there are thousands of unhoused persons in LA County and we are spending $700,000 to assist one person or, at best, one family.”

Calaycay advocates finding different avenues, mentioning LifeArk, a Duarte company that uses prefabricated, recycled plastic units in developing permanent support housing units and transitional housing. He said the cost of the company’s transitional housing is about $80,000 per unit. “I think that’s more realistic,” he said.

Another concern is the city’s rental situation. Calaycay believes directing funding to help renters — as in the city’s Temporary Housing Stabilization and Relocation Program — can “impact more people than building one unit for upwards of $700,000.”

Calaycay said the most challenging problem in getting community buy-in for new housing developments stems from the state’s high-density “cookie cutter,” approach, common in cities like Westwood, and increasingly, Pomona. “Ironically those developments if you go check the … market prices right now, I think most people would consider that hardly affordable, even then for all this high-density development they’re bringing.

“One argument of affordable housing proponents is that people should have housing near to where they work,” Calaycay wrote in an email. “The idea is to reduce commutes and even to try to encourage people to give up their cars.” He wrote City of Industry, a hub for jobs, “has not been required to build housing. Communities like ours have been expected to absorb the housing responsibilities for communities that may be job centers, but don’t have housing in their city. Tying that into the transportation system statement, Southern California has been built in such a sprawled out fashion that transportation lines don’t always run conveniently adjacent to where people live and work.”

Asked what the council does well, Calaycay said the members’ mix of life experiences and philosophies are a good representation of Claremont as a whole. He also said the council does a good job of balancing its governmental demands with allocating resources fairly.

He added differences of opinion among council members can sometimes slow things down in an already slow-paced government process. “Water’s becoming a central issue again with the proposed increases,” Calaycay said. “The point being that when you have a big issue like that, you really kind of need a strong united bond, particularly philosophically, and at times if you don’t have that sometimes it’ll take longer to move things along. It can be challenging … but I’m not going to characterize it as necessarily a completely bad thing.”

Calaycay faces challenger Rachel Forester on November 5.

Calaycay’s campaign website is at coreycalaycay.com.

0 Comments