City begins redrawing of council district maps

by Steven Felschundneff | steven@claremont-courier.com

It may seem like déjà vu all over again but on Tuesday the City of Claremont officially began the process of drawing new council district maps.

Just three years ago the Claremont City Council adopted the current map after voting in November 2018 to transition from at-large to district-based elections. However, those districts were based on 2010 U. S. Census data and by federal law must be redrawn to reflect demographic changes revealed by the 2020 Census.

Over the next few months Claremonters will have numerous opportunities to help redraw the maps by participating in workshops and by creating and submitting their own maps from the city’s online redistricting portal.

The first public hearing on the matter took place at Tuesday’s city council meeting, during which Robert McEntire of National Demographics Corporation provided an overview of the timeline along, with an explanation of the federal and state laws that direct and define the process.

The second public hearing will be a community workshop on Saturday, January 29 at 10 a.m., during which the public will receive further education on redistricting and participate in a discussion of mapping tools. February 8 is the deadline for submission of draft maps, followed by the third public redistricting hearing during the city council meeting on February 22, when the draft maps will be discussed.

The city must publish revised draft maps on March 1, seven days ahead of the council’s March 8 meeting at which time the final map will be selected and an ordinance passed.

Claremont leaders chose to proactively transition to five council districts in 2018 following a string of demand letters sent to other California cities warning that at-large elections violated the state’s Citizens Voting Rights Act (CVRA) passed in 2001. That law sought to remedy a situation in which “minorities and other members of protected classes were being denied the opportunity to have representation of their choosing at the local level because of a number of issues associated with at-large elections,” according to a districting fact sheet published by the city.

Following a contentious selection process, the council narrowly approved its initial map in February 2019. Drawn by National Demographics Corporation, that map featured both “regional” and “vertical” components, and divided some traditional neighborhoods. The vertical components, as the name suggests, linked neighborhoods in the different parts of town to promote cooperation and avoid dividing the city into blocks of economically advantaged and disadvantaged voters.

Redistricting will largely be an exercise in rebalancing the current districts to bring the city into compliance with state and federal statutes. The most important of these is adjusting the district boundaries so there is less than 10% difference between the most and least populous.

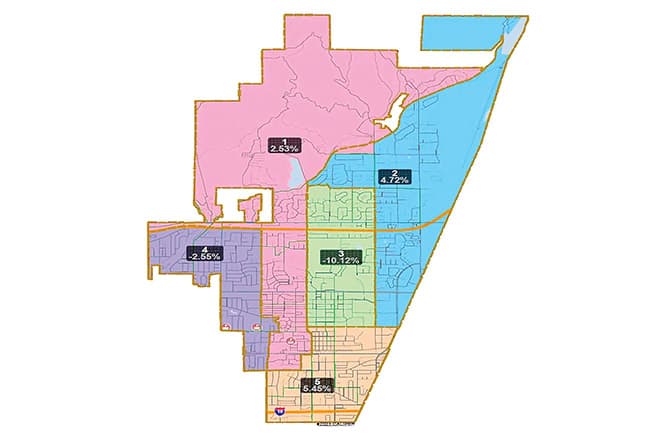

According to McEntire’s presentation, District 3, which forms a rectangle in the middle of the city including portions of the Village and neighborhoods north of Base Line Road, has lost 10.12% of its population over the last 10years. In contrast, District 5, which also includes part of the Village and also encompasses all of south Claremont, has increased its population by 5.45%, for a cumulative gap of 15.57%.

However, it is not as simple as moving roughly five percent of District 5’s population to District 3, because District 2 experienced a 4.72% increase and District 1 is up 2.53%, while District 4 is down 2.55% (see map for boundaries).

Claremont is in the unusual position of having three of its councilmembers — Jennifer Stark, Mayor Jed Leano and Mayor Pro Tem Ed Reece, who were all elected in the city’s final at-large election — up for reelection in 2022. Corey Calaycay, who represents District 1, and Sal Medina, District 5, were elected during the first district election in 2020.

Sitting councilmembers cannot have their term shortened by redistricting, so the westernmost portion of District 1, where Calaycay lives, must stay in that district. Other items of consideration include avoiding gerrymandering by preserving geographically contiguous shapes, keeping the new districts as close to their current outlines as possible and using natural landmarks for boundaries. Less easy to define, but just as important, are respecting existing communities of interest, which could be a shared school district or an established neighborhood, as well as a similar ethnicity or race.

The law also requires that any protected class or group of voters be protected, which means redistricting cannot spread that demographic out to dilute its voting power or pack it into the smallest area possible for the same effect.

During public comment, former councilmember Larry Schroeder, who lives on Indian Hill Boulevard, expressed interest in using redistricting to reunite the Claremont Village which was split up under the districting process. While on council Schroeder voted against the current map for this same reason. Longtime Claremont resident and former councilmember Karen Rosenthal expressed similar views, saying, “A major historic district has been divided in half.”

In what may be a harbinger of how the process will play out, less than half a dozen people spoke during public comment, in spite of the fact that this is one of two opportunities for residents to make their wishes known before the development of the maps begins.

District 3 will almost certainly become geographically larger, spreading into districts 1, 2 and 5, all of which saw an increase in population. This creates an odd situation in which some Claremont residents who voted in districts 1 and 5 in 2020 will get to vote again in the current election because they will now be in District 3. Conversely, any voters who shift from districts 2, 3 or 4 into 1 and 5 when the boundaries are moved will ultimately sit out two elections in a row.

McEntire said that if the council moves people up to where they get to vote again, that is not a problem, but certainly if you make them wait longer between when they would vote then it’s like disenfranchisement.

“It’s not illegal but it leaves people feeling disengaged from the process, and that of course would be the worst possible outcome,” he said. “But it’s a little bit unavoidable in small portions, because of the way the law is created.”

Jennifer Jaffe expressed her desire to see the city go back to at-large elections, a view that was shared by others including Stark.

“I hope every effort will be made for us to return to being just Claremont voters,” Jaffe said.

“In 2019 when we entered into districts as a proactive attempt to be right with CVRA we also stipulated that if there was a pathway to go back to at-large that we would consider that. And I was just wondering if that was going to weigh into this discussion?” Stark asked.

City attorney Alisha Patterson responded that Claremont did put a provision in the current ordinance that if the nature of the law changed, the council would have the opportunity to consider reverting back to at-large elections.

She cited the City of Santa Monica’s current challenge to districting under CVRA, which, although no hearing date has been scheduled, will come before the California Supreme Court at some point.

“We have had some pretty major legal developments that are not completely done at this point,” Patterson said. “Until we get some guidance from the California Supreme Court, I think everybody is just waiting. And even if that case is upheld, we would still need to look at Claremont’s individual data and circumstances to see if we are truly similar to Santa Monica or not.”

0 Comments