Mother and daughter share rich family legacy

by Steven Felschundneff | steven@claremont-courier.com

Sumner Danbury principal Rahkiah Brown’s great-great-great-grandfather, Richard Brock, was given to a Virginia woman as a wedding present. Born into slavery in 1824, Brock was essentially part of this woman’s dowry, and he was subsequently transported to Houston, Texas when she moved there a short time later.

Brock was an enterprising man, so after working for the Virginia woman’s family all day, he took up blacksmithing at night to earn enough money to buy his family’s freedom.

“He paid for his freedom, he paid for his wife’s freedom and his sister’s freedom,” Brown said.

After the Civil War ended, Brock continued operating his blacksmith shop, bought property and soon began to engage in Houston’s Black civic life. He became the first Black alderman, co-founded the first Black Masonic lodge and, in conjunction with other former slaves, Brock launched the first Black church and the first Black cemetery. A Houston elementary school and a park are named in his honor.

In 1872, Brock, Richard Allen, Jack Yates, and Elias Dibble bought 10 acres of land for $800, creating Emancipation Park as a place to hold Juneteenth celebrations commemorating the end of slavery. In 1916 the land was donated to the City of Houston and for decades it was the only park in the city that welcomed Blacks, according to the Emancipation Park Conservancy.

Brock died in 1906, however, his family continued to make history. Tracing their steps from the end of reconstruction in Texas, they migrated to Massachusetts after World War II to escape Jim Crow laws, fought for justice during the civil rights movement and returned to Texas as integration began in the Northeast.

Brock’s great-great-granddaughter, Evonne Brown is Rahkiah’s mother and the current matriarch of the family. Evonne’s was born at Camp Lejeune in North Carolina on August 15, 1944 where her father was serving in the first Black Marine unit. A few months later the family moved to Somerville, Massachusetts where Edward Brown took a railroad job.

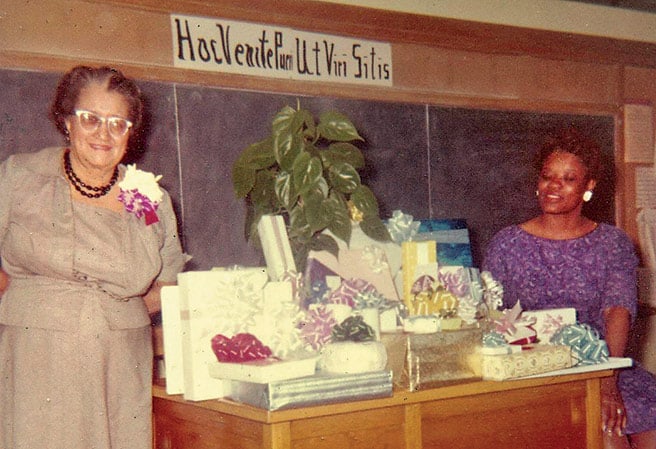

The family has a legacy of highly educated, strong women, including Evonne Brown, her mother Portia Smith-Brown and her grandmother Ilma Smith who all received master’s degrees.

“You could not even get a bachelor’s if you were Black, they called it a normal degree,” Evonne Brown said about Smith. “They could not go to the University of Houston so they set up something for [Black] people who wanted higher education.”

“Back in the 1920s she received her master’s degree when most Black people were delegated to roles of domesticated jobs,” Rahkiah Brown said of her great-grandmother.

The degrees were backed by the university, which allowed Smith to teach. She was on the founding faculty at Wheatley High School in Houston where she taught Latin for 49 years. Smith organized the Wheatley Loveable Troubadours, a service club on campus that fed both the home and visiting football teams.

“Boys were good players but had no food or clothing,” Smith told the Forward Times newspaper. “The girls prepared lunches for those boys who could not afford them. And when visiting teams came the same girls prepared food for the visitors.”

“My grandmother was feeding everybody during the depression,” Evonne Brown said.

As an educator, Rahkiah Brown looks to Smith as a role model because she was a champion for the students who came through Wheatley. Pulling out a class picture she points to Smith, who is standing in the center surrounded by the students and faculty.

“The principal is not in the middle of that picture, my great-grandmother is,” Rahkiah Brown said. “Because of all the work she’s done to change the school, to support the students and start a free lunch program to make sure every kid was fed. To make sure kids were clothed.”

“I am proud of who I am and where I come from because not many people have that type of legacy,” she continued. “And I know that I come from a line of leaders and innovators. People who are not afraid to take a stand and stand up for what you believe in.”

According to her great-granddaughter, one reason Smith was so successful and accomplished during the Jim Crow era in the South was her light complexion.

“You have the segregation within Black culture, too, with the skin color. So she was able to pass for White and in a lot of instances she was able to go to places where it was Whites only,” Rahkiah Brown said.

“My mother told me that at Emancipation Park they had a pool and in the morning the light-skinned Blacks could use it and the afternoon and evening was only for the dark-skinned people … at the park that Richard Brock started. But that is what they had to go by,” Evonne Brown said.

During a visit to Houston when she was six, her godmother decided to take Evonne shopping. However, Evonne was not accustomed to the strict parameters Blacks had to live by in the South, including sitting at the back of the bus.

“I just sat wherever I wanted to, and all of a sudden it was so quiet. I looked around, wondering why people are looking at me, the shock on my godmother’s face to see me sitting behind the bus driver. She grabbed my arm and my feet did not hit the floor until we were off the bus,” Evonne Brown said.

She described the segregation in Massachusetts made her feel invisible, so just after Rahkiah was born in 1977, mother and daughter returned to Houston, settling in a middle class neighborhood called the Third Ward.

“In the north there was racism and segregation, but not like it was in the south,” Evonne Brown said. “I wanted to leave Boston because I was tired. I lived in a White world there and I wanted to be around my people more. And that is why I moved to Houston because we were only 2% of the population in Cambridge.”

In Houston, Evonne Brown took a job as a social worker with the state of Texas investigating reports of abused children under age six.

“All my life I have been dedicated to working with children, even though I got my degree in gerontology,” she said.

About twenty years ago Evonne followed Rahkiah out to California when the younger Brown decided to attend California State University Los Angeles and pursue acting. Rahkiah continued to act even as her career in education grew.

In the 1960s Evonne Brown fought for the equal rights of Black people and the passage of the 1965 Civil Rights Act, participating in boycotts, marches and sit ins at Woolworths. She recalled that during those marches the participants were largely Black.

Last year Rahkiah received a phone call from her mother who was in tears after seeing a Black Lives Matter protest on television with participants of all colors and races.

“Watching my mother cry from that, it moved me because I understand when people say ‘Oh we haven’t gone anywhere’ but we have gone somewhere. We have made progress. Because people are coming together regardless of the color you are, regardless of your race. It’s slow progress and people don’t see it and it’s not immediate but there is a change,” Rahkiah Brown said.

Other news stories, including the killing of George Floyd, made Evonne feel like society had taken a step backward.

“Today what I really feel is more sadness than anything else. Looks like for every step forward, we have to go back two steps. But my cup is always half full never half empty, and even though we might be taking a step backward we are still going to move forward,” she said. “We can’t stop everything, stuff is still happening, but we are being heard. People are doing something. I don’t know what it will be like in my granddaughters’ time but it gives me hope that it will be better. It may never be good but it will always be a little bit better.”

0 Comments