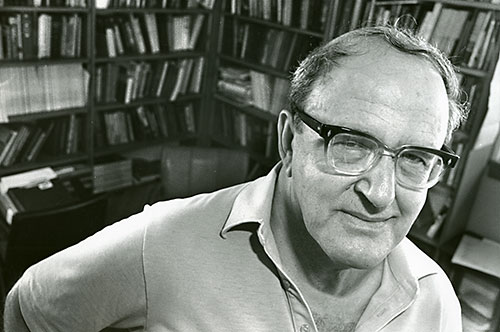

Harry V. Jaffa: Influential political philosopher

Influential political philosopher, Lincoln scholar

Harry V. Jaffa, professor emeritus at Claremont McKenna College and the Claremont Graduate University, died on Saturday, January 10, 2015 at Pomona Valley Hospital. He was 96.

Mr. Jaffa was born in New York City on October 7, 1918 to Arthur and Frances Landau Jaffa and grew up in Long Island. After earning a bachelor’s degree in English from Yale University, he took a job in Washington, DC. There, in the dining hall of a boarding house, he met Marjorie Butler, who was among the first wave of employees called to Washington, DC to help staff the newly built Pentagon. They were married on April 25, 1942. Mrs. Jaffa would be an unflagging support for her husband over the years, helping him prepare his manuscripts and tending to finances while he was immersed in the world of ideas.

In 1944, the couple moved to New York, where Mr. Jaffa earned a PhD at The N

“His discussion of Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics just blew me away. It was like the Gospel for a Baptist preacher. All my life had been a preparation for that moment,” Mr. Jaffa told the National Review in 2009. He had found a mentor and his calling.

“In the mid-20th century, there was a tendency in political science to try to turn everything into statistics,” said John J. Pitney Jr., the Crocker Professor of Politics at Claremont McKenna College. “Harry was part of a movement to make this study of political principals the focus of political science.”

After receiving his PhD, Mr. Jaffa’s career as a political science professor led him first to the University of Chicago and then, from 1951 to 1964, to Ohio State University. Beginning in 1964, he spent 25 years on the faculties of Claremont McKenna College and Claremont Graduate School. During his years in Claremont, he founded the Winston Churchill Association and served on the board of directors and as a distinguished fellow of The Claremont Institute for the Study of Statesmanship and Political Philosophy, where he remained active until his death.

“He liked to talk about how his life changed when he met Leo Strauss, that Strauss was a pied piper. But no one was as much of a pied piper as my father,” Mr. Jaffa’s son Philip said. “He not only recruited students from the various universities he taught at. He got two of his childhood playmates, Joseph Cropsey and Frank Canavan, to become professors of political philosophy.”

Brian Kennedy is the president of The Claremont Institute, of which Mr. Jaffa is said to be the intellectual founder. He said the Claremont Colleges were always great schools, but their political prominence grew once Mr. Jaffa arrived. “Jaffa was such a prominent scholar on Abraham Lincoln, graduate students from all over America wanted to study with him.”

Mr. Jaffa became interested in Lincoln as a PhD student when he found a copy of the Lincoln-Douglas Debates in a used bookshop in Manhattan. In 1959, he published Crisis of the House Divided: An Interpretation of the Issues in the Lincoln-Douglas Debates.

Andrew Ferguson, senior editor of The Weekly Standard, wrote that Crisis of the House Divided “is a book that will never die—a genuine landmark in American thought. It is the greatest Lincoln book ever.”

At the time of its publication, Lincoln had been relegated to the status of charismatic icon. “Everybody talked about his life but didn’t talk about his ideas,” Mr. Kennedy said.

“No one in 75 years had treated Abraham Lincoln’s political thought seriously,” Philip Jaffa agreed. “Lincoln was a man who spent his time defending ‘the Laws of Nature and of Nature’s God’ as the basis of self-government. My father singlehandedly resurrected Abraham Lincoln as a political thinker in the American political tradition.”

That presentation of Lincoln’s thought led to an ever-expanding interest in the American Founding and the principles of the Founding Fathers. “It was like a snowball rolling downhill,” said Philip. “My father is not responsible for all the snow that attached to it, but he is the one that launched it on its journey.”

Other books included Thomism and Aristotelianism, Original Intent and the Framers of the Constitution and works of his collected essays such as The Conditions of Freedom, How to Think About the American Revolution and Equality and Liberty. His last major work was the long-awaited sequel to his earlier Lincoln book, A New Birth of Freedom: Abraham Lincoln and the Coming of the Civil War, published in 2004.

One of Mr. Jaffa’s biggest claims to fame was coming up with two lines uttered by Barry Goldwater when he accepted his nomination for president at the Republican National Convention of 1964: “I would remind you that extremism in the defense of liberty is no vice. And let me remind you also that moderation in the pursuit of justice is no virtue.”

Some might think Mr. Jaffa’s allegiance was to conservative principles, but his only real allegiance was to the philosophic quest, according to Philip. “My father once asked me, ‘Do you know what the greatest line in philosophy is? It’s not when Socrates said, ‘Know thyself.’ It’s when Aristotle said, ‘Plato is a friend but a dearer friend is the truth.’”

No one’s assertions were above scrutiny.

“My father was part of the conservative movement, but he spent a good deal of his professional life criticizing conservatives—he was the proverbial skunk at the garden party,” Philip said. “He was a meticulous scholar. If people didn’t do their homework, he was going to point out their mistakes, no matter who they were, no matter where they were.”

Philip recalled accompanying his father to a lecture at a conservative organization, where he had taken a fee and had prepared a paper that he was going to discuss. When he got behind the podium, he pointed out a large sign hung on the wall: “That government is best which governs least—Thomas Jefferson.” Dr. Jaffa pointed out the sign, read the words, and then added: “There are only two things wrong with that. The first is that it isn’t true, and the second is that Thomas Jefferson never said it.”

In the forward to one of Mr. Jaffa’s books, William F. Buckley, Jr. quipped, “If you think Harry Jaffa is hard to argue with, try agreeing with him. He studies the fine print in any agreement as if it were a trap, or a treaty with the Soviet Union.”

“He would keep on debating no matter what,” Mr. Kennedy agreed. “He wasn’t trying to be argumentative. He was really the kind of guy who wanted to get at the truth. That’s a rare thing these days.”

Mr. Jaffa wasn’t all about work. He loved to laugh and was an exercise and sports enthusiast. He put in thousands of miles cycling, sometimes on his own and at other times riding a tandem bike with his wife, the late Marjorie Jaffa. His happiest hours, however, were taught imparting the art of questioning.

“He was one of the most loving decent human beings you’d ever want to meet, just at level of wanting to teach students. He wanted to spend whatever time he could with them, just to make them better,” Mr. Kennedy said.

Mr. Jaffa is survived by his children, Donald Alan Jaffa, Philip Bertran Jaffa and Karen Jaffa McGoldrick, and his three grandchildren, Peter Anthony Jaffa, Nicholas Andrew Jaffa and Frances Karoline Maria Ella Kerstin Jaffa.

His funeral will be held today, Friday, January 16, at 1:30 p.m. at Todd Memorial Chapel, 325 N. Indian Hill Blvd. in Claremont.

0 Comments