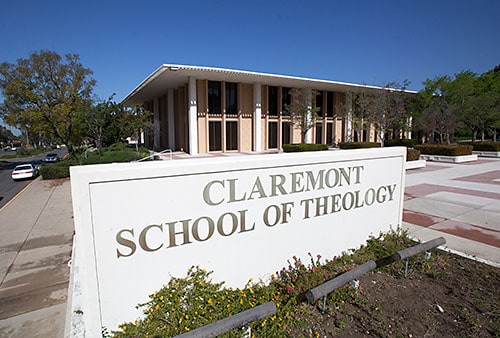

Schools part ways as Claremont Lincoln seeks accreditation

A well-known Claremont couple is splitting up. On Monday, April 21, the Claremont School of Theology sent out a press release announcing it is ending its relationship with Claremont Lincoln University.

Trustees of the Claremont School of Theology “ask all who care for the seminary to hold both schools in prayer as they move forward on separate paths.”

The release is not a bombshell, according to Rev. Dr. Jeffrey Kuan, the 7th president at Claremont School of Theology. Instead, he says it is simply making public a parting of ways that is already underway.

“The decision for separation actually began with Claremont Lincoln University when they began to seek their own accreditation and to become independent, to be no longer embedded at Claremont School of Theology,” Rev. Dr. Kuan said. “We had no decision over that. It was a Claremont Lincoln University decision.”

Jerry D. Campbell is the 6th president of the Claremont School of Theology and the founding president of Claremont Lincoln University. He says the plan for the school—which has been recognized as a candidate for accreditation by the WASC Senior College and University Commission—has always been for it to become an independent, freestanding institution.

“That’s why it was initially incorporated as a California corporation,” he said.

As in the dissolution of any union, there’s a bit of a he-said, she-said quality to the schools’ estrangement.

CLU’s curriculum has been significantly streamlined in recent months. Originally, the school planned to offer master’s degrees in ethical leadership, interreligious studies, interfaith chaplaincy and interdisciplinary or comparative studies, as well as doctoral programs in practical theory and religion.

CLU now only offers a master’s degree in ethical leadership. Master’s degrees in interfaith action and social impact are said to be in the works, according to the Claremont Lincoln University website.

All other programs are being phased out, though the CLU site notes that some may still be offered through the Claremont School of Theology.

Trustees and administration at Claremont School of Theology maintain that such changes are a sign that Claremont Lincoln University has opted to “move away from its interreligious roots and become a secular-focused university.”

Mr. Campbell begs to differ. The term secular is “a slight misunderstanding,” he said. Religion, he emphasizes, is the whole point of a Claremont Lincoln University education.

“We don’t teach Christianity or Judaism or Islam or Jainism or Buddhism,” Mr. Campbell said. “We teach you how to lead across those groups, and how to bring those groups together.”

If a student wants to gain a deeper understanding of a particular faith, or to be ordained as a minister, rabbi, cleric or other religious leader, Mr. Campbell said they are encouraged to do so through one of Claremont Lincoln University’s partners.

Currently, that consortium includes the Claremont School of Theology; the Buddhist University of the West; The Academy for Jewish Religion, California; and Bayan Claremont, an Islamic graduate school being established by the Islamic Center of Southern California with the help of Claremont Lincoln University and under the umbrella of the long-accredited CST. Claremont Lincoln University organizers hope the consortium will expand to include an institution representing Roman Catholicism as well as Protestantism and those dedicated to Sikhism, Jainism and Hinduism.

The Claremont Lincoln University website still lists the Claremont School of Theology as a member of its consortium. The Claremont School of Theology board will meet on May 20 to vote on whether or not they will continue the partnership.

“Claremont Lincoln is very much a consortium-related institution because [the school] itself doesn’t teach a particular religion. That’s what its collaborators teach,” Mr. Campbell said. “If CST chooses not to collaborate in the consortium, we will have to find [a new] Christian partner.”

Dr. John Cobb, emeritus professor in theology at Claremont School of Theology, emphasizes that since he is retired, he is only an observer of the differences that have arisen between the two schools. While he doesn’t think CLU organizers intended to be misleading, he believes the administration and staff at CLU may feel they were sold a bill of goods.

Staff and administration once assumed that the fledgling school would be run like a liberal arts institution, Dr. Cobb said. With the use of adjunct faculty and the preponderance of online instruction, he characterizes Claremont Lincoln as embracing a “corporate model” of education.

“If the people at CST had known this from the beginning,” Dr. Cobb said, “they would never have gotten started [with the partnership].”

CST staff members—who helped develop many of the degree programs CLU once planned to offer—thought they would have a greater amount of input in the development of Claremont Lincoln University, Rev. Dr. Kuan agreed. There are now no tenure-track professors on the CLU staff, nor are there any instructors from the Claremont School of Theology.

“If you go into their website, the previous faculty listed have all been removed,” Rev. Dr. Kuan said.

The fact that Claremont Lincoln University is planning to offer an increasing amount of classes online is also troubling, the administrator confirmed.

“I can’t imagine wanting clergy out in the world without having the experience of being face-to-face with faculty,” he said.

Mr. Campbell said that while he is disappointed that more CST faculty are not on the staff of CLU, that development is a result of the nature of the institution. It is crucial for Claremont Lincoln University to forge partnerships with many instructors deeply immersed in an array of belief systems, he said.

As far as the online question goes, Mr. Campbell said it’s a matter of practicality.

“Even in the early days, our partners have been scattered all over the Los Angeles area,” Mr. Campbell explained. “If you have to drive from Claremont to the west side or vice versa, it is quite a commitment. And the question becomes, educationally, how does Claremont Lincoln make it fair for all of the collaborating partners to have easy access to the same materials?”

Claremont Lincoln University has no intention of denying its students face-to-face interaction with instructors, Mr. Campbell corrected. “We’ll put the coursework online and then supplement it with what we call summits, where we get together for a week and get to meet and interact with each other.”

Claremont School of Theology, which moved to the City of Trees in 1957, traces its history to 1885 with the founding of Maclay College in San Fernando.

Language in the CST release—“Claremont School of Theology’s historic connection with the United Methodist Church played a major role in the decision to end the relationship with Claremont Lincoln University”—makes it inevitable that some observers will see the school’s decision to separate from CLU as parochial.

The Rev. Dr. Kuan, however, insists this is not a case of CST rejecting interreligious studies. He noted that the school plans to maintain strong relationships with The Academy for Jewish Religion, California, Bayan Claremont and are in the process of strengthening further interfaith partnerships.

“Frankly, the vision of interreligious education has been very much a part of the DNA of Claremont School of Theology,” he said. “There is already a readiness on the part of the faculty to move in this direction of interreligious education.

“We are not giving up on what we believe needs to be the theological education model for the 21st century,” Rev. Dr. Kuan continued. “We are going to do it now without the encumbrance of a structure that did not work.”

Mr. Campbell still has faith in the practicability of Claremont Lincoln University, which he says will help desegregate theological education.

“In the past, what’s tended to happen is each religion teaches its own future leaders,” he said. “We have religious conflict because part of the curriculum has never been ‘How do you get along with, collaborate with and work with people of other religious traditions to solve common problems?’ We want to change that.”

Each school president has said he wishes the other institution Godspeed as it moves towards its goals.

In the meantime, like all couples whose relationship is at an end, the institutions have begun separating their affairs. For instance, Claremont Lincoln University, once housed on the CST campus, has obtained offices in the village, as having a separate office is a requirement of accreditation.

“From some points of view, [the separation] is a great tragedy,” Dr. Cobb said. “The danger when a division takes place is that people are angry and blame each other, and there’s not much point in any of that.”

Perhaps it is best for the two schools, with their differing models of education, to diverge, he said.

“Maybe the two institutions can live side-by-side and overlap and make contributions to each other,” Mr. Cobb said. “That’s what I hope will come out of it.”

—Sarah Torribio

storribio@claremont-courier.com

0 Comments