From Germany to Shanghai: a Holocaust survivor’s story

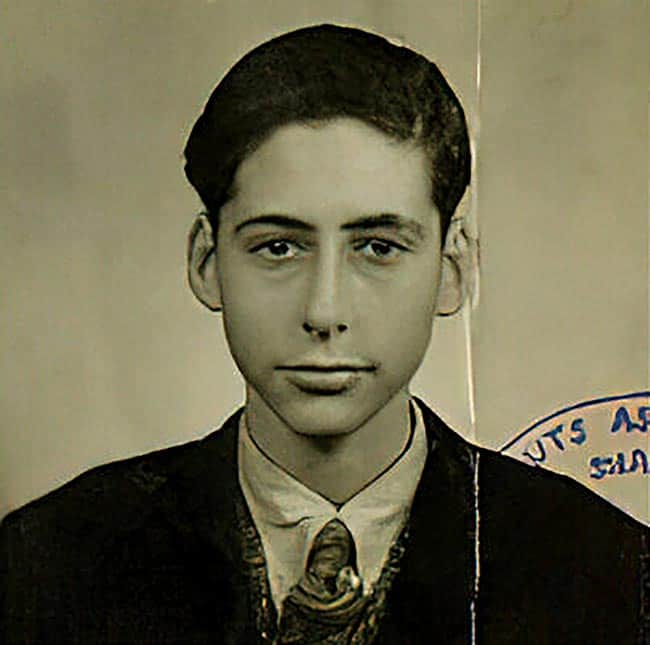

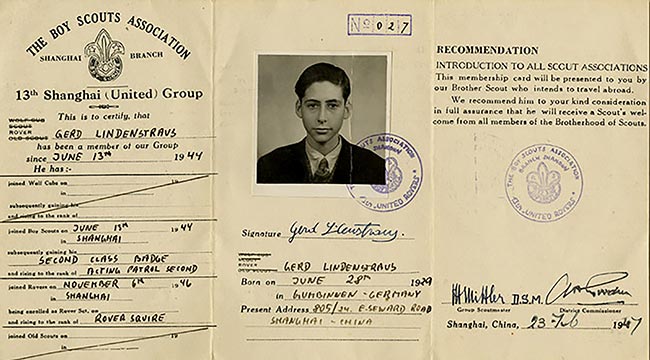

Jerry Lindenstraus is pictured here in his “Boy Scouts Association, Shanghai Branch” photo from 1944, when he was 14. Now 93, Lindenstraus cautions young people to “Keep your eyes and ears open” to newly resurfacing Nazi ideologies in the United States. Photo/courtesy the collection of the Museum of Jewish Heritage

by Jenny Wang | special to the COURIER

In August 1939, 10-year-old Jerry Lindenstraus and his Jewish family of eight arrived at the port of Shanghai, China carrying some luggage, German family heirlooms, and fears about their future.

Jerry’s spirit remained animated as he inhaled the steamy summer air and surveyed the boisterous crowd of Asian faces. He and his family were then taken to the Jewish refugee center via trucks –– nine of the 18,000 Jews who sought refuge in Shanghai during the terrible rise of Nazi Germany.

Now at the age of 93, Lindenstraus can still recall in vivid detail his experiences as a Jew during World War II. He recently sat down with students from the School of the New York Times to recount these memories in hopes that his story will inspire future generations to actively combat not just antisemitism, but ongoing anti-Asian hate, gun violence, and other atrocities.

“I’m worried not so much for me, but for my grandkids.” he said.

Lindenstraus was born and raised in Gumbinnen, a small German town of about 30,000. His grandfather served as the head of the Jewish community while his father ran a profitable family department store.

Their comfortable living was disrupted, however, when the Nazi Party rose to power in 1933. With their swastika armbands, S.S. officers, and constant parades, “They made it a point of being visible,” Lindenstraus said.

The escalating hostility toward Jews drove his family to move to Konigsberg, the capital of then East Prussia (territory now divided between Poland and Russia). Then came the dreadful night of Kristallnacht, also known as the Night of Broken Glass, when Nazi forces systematically vandalized thousands of Jewish synagogues, homes, and stores across Germany and Austria.

“I didn’t see the flames because it was at night,” Lindenstraus said, “but when I tried to go to school the next day, it wasn’t there anymore.”

Reading this event as a sign to leave, his father, Louis, soon secured nine first-class tickets for the last German steamship to Shanghai, which was the only city without visa requirements at the time. All other European countries, as well as the US, harbored heavily antisemitic policies that denied visas for Jews.

His father had sent 500 British pounds, today’s equivalent of roughly $25,000, to a cousin in London, with the agreed arrangement that he would later send the money to Shanghai for the family to use for living. After a grueling one-month sea voyage, the Lindenstraus family finally reached their destination.

At the time, Shanghai was controlled by various foreign powers and divided into French, British, and Japanese independent settlements. The city saw itself stripped away from Chinese jurisdiction and influenced by both eastern and western cultures.

“Anything went on in Shanghai,” said Lindenstraus. “They had opium dens, they had rickshaws, night clubs, professional beggars.”

Jerry Lindenstraus is pictured here in his “Boy Scouts Association, Shanghai Branch” photo from 1944, when he was 14. Now 93, Lindenstraus cautions young people to “Keep your eyes and ears open” to newly resurfacing Nazi ideologies in the United States. Photo/courtesy the collection of the Museum of Jewish Heritage

As the family adjusted to their new life, they learned of their cousin’s betrayal: he had lost 400 of their 500-pound nest egg. It was devastating news. With their prospects seemingly shattered, his father soon developed pneumonia. He died just months after their arrival, leaving young Lindenstraus and his stepmother Lillie to fend for themselves.

With his birth mother in Colombia, his stepmother became his mother figure. They rented a cheap apartment in the Jewish ghetto of Hongkew District and sold precious family heirlooms to bring food to the table. The Sephardic Jewswho immigrated from Iraq about a hundred years prior also generously lent help to the refugees, utilizing their resources and connections in Shanghai’s big businesses.

Despite the limitations, he was quick to adapt to the new environment. He became fluent in English through the Shanghai Jewish Association school, and readily learned to speak Pidgin — a mixture of English, German, and Chinese –– to bargain with the locals. He joined the British Boy Scouts, attended Congregation Ohel Moishe, and met his lifelong best friend, Gary Kirschner.

Nevertheless, Lindenstraus acknowledged the grim circumstances.

“Shanghai-landers always minimize how bad it was, but it was pretty bad, especially for the adults,” he said.

Tropical diseases ran rampant, and his stepmother never fully recovered from the illness she contracted in the ghetto. Many fell sick even after boiling the drinking water they had purchased. Refugees needed special passes for traveling outside the ghettos, for which they had to stand in the heat for long periods of time and endure humiliation from Officer Ghoya, nicknamed the “king of the Jews.”

“I learned to be a survivor,” Lindenstraus said.

On September 2, 1945, the Japanese government officially surrendered, marking an end to World War II. The retreat of Japanese forces in Shanghai finally freed the Jewish people there from the ghettos, a moment cherished by Lindenstraus as one of his fondest memories.

He emphasized the importance of hope and resilience during difficult times. When asked about his feelings on having survived while so many others perished, he answered, “I didn’t feel guilty. I felt lucky.”

After the war, Lindenstraus reunited with his birth mother in Colombia and lived there for seven years. He then traveled back to Germany and later moved to New York, where he met his wife, Erika.

His unique experiences and fluency in English, German, and Spanish, allowed him to successfully launch his own business exporting automotive parts to Latin American countries.

He eventually returned to Shanghai with his son Leslie to visit the ghettos where he lived as a teen, this time as a speaker at the Shanghai Jewish Refugee Museum. Even during the pandemic, Lindenstraus did not lose his connection with the city, giving Zoom talks to the Shanghai congregation of Jewish businessmen and closely following the city’s pandemic news.

Despite the adversities, his optimism played an instrumental role in his survival, as it did with his success in his later life. Now, as Nazi ideologies resurface in the American political spectrum, Lindenstraus feels compelled to tell his story and share advice with younger generations.

“Keep your eyes and ears open,” he said. “And make sure to be involved and active [in your community] so that these things don’t happen again.”

Jenny Wang, 16, is a junior at The Webb Schools, where she is the copy editor of the Webb Canyon Chronicle. This past summer she attended the New York Times reporting program, and this story is her culminating project. Jenny plans to study international relations and journalism in college, hopefully at Stanford University.

0 Comments