Cash Whiteley is a man

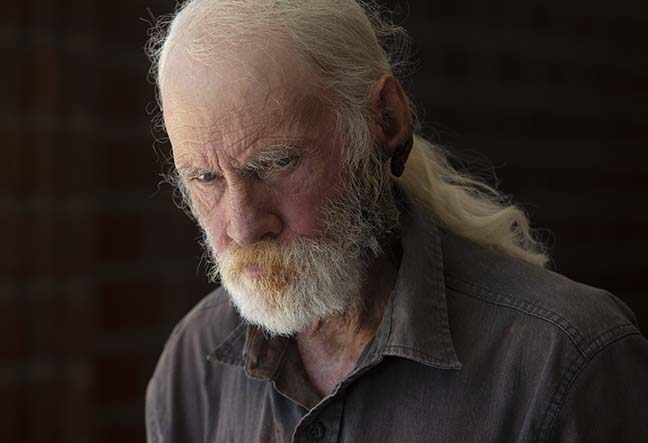

Cashman “Cash” Whiteley, 59, has been unhoused for 22 years. He sleeps most nights on the grounds of a Claremont church. Despite several treatment attempts at local hospitals and doctors’ offices, an infection on his jaw has been spreading for four years and has now made it impossible to eat. Courier photo/Steven Felschundneff

by Mick Rhodes | editor@claremont-courier.com

Cashman “Cash” Whiteley has been fighting his whole life.

The 59-year-old unhoused man sleeps most nights on the grounds of a Claremont church.

“There’s not as many ants there as there are at other places,” Whiteley said. “I can’t get ants in all this,” he said, pointing to the gruesome open wound on the left side of his face.

In 2018 an unhoused woman intent on killing him hit him in the face with a large rock. The infection, which Whiteley believes to be in his gums, emerged weeks later. Aside from a few courses of antibiotics, he’s had no relief since.

The pain is excruciating, making sleeping more than a couple hours per night near impossible. The risk of infection is constant. It’s now progressed to the point where he can’t eat solid food because it’s agonizing to open his mouth and chew.

“I’ve been to six emergency rooms and have been treated over 13 times,” Whiteley said. “Some of the emergency rooms I went to two different times. They just tell me go to my regular doctor.”

According to Whiteley, the routine has been to see his regular doctor, at East Valley Community Health Center in Pomona, who then sends him to another doctor, that doctor to another, and so on. He eventually winds up with an appointment with a specialist in Los Angeles. But his Tri-Cities Mental Health Services affiliated social worker isn’t permitted to transport him out of the facility’s Claremont/La Verne/Pomona-area coverage area.

It’s a tragic round-robin loop of failure, on repeat, with Whiteley’s suffering compounding all the while.

Most of the doctors and physician’s assistants who’ve seen his wound believe it to be skin cancer. Others say cellulitis. Regardless of the diagnosis, the bottom line is Whiteley needs immediate medical attention for the open wound.

“I’ve had three doctors say I need to be hospitalized, but I’m not hospitalized yet,” he said.

Cashman Whiteley, a local unhoused man, stands in the shade of the entrance to St. Ambrose Episcopal Church on Tuesday. Courier photo/Steven Felschundneff

But what about the Hippocratic oath?

“That’s unless you’re homeless,” Whiteley said. “If you’re homeless, who cares? The state doesn’t pay them enough money to help me, apparently.”

Asked how this ever-deepening cycle of suffering makes him feel, Whiteley answered the only way he seems capable: with brutal honesty.

“It makes me feel like I have always felt: not worth anything,” he said. “And the bad part is, they’ll look at you and say, ‘You’re right. You’re not worth anything.’”

Tragically, it seems Whiteley’s course was set early on.

Born in Madera, California, the county seat of Madera County about 50 miles north of Fresno, he grew up nearby on a small cattle ranch. He doesn’t want to talk much about his family.

“I was thrown out in the street at 17 years old,” Whiteley said. “I went to work for the carnival because it was all I could get. I have literally been kicked around, told I’m inadequate and I’m no good from the time I can remember. My mother always said, ‘Go away. You bother me. You’re just like your father, no good.’

“It’s all I’ve ever heard.”

He’s worked a series of odd jobs for months at a time — in carnivals, pizza parlors, Christmas tree lots, and dozens of others — since leaving home at 17. He said his ADHD diagnosis is partially to blame for his inability to hold a job.

“So, I never really made any money,” Whiteley said. “I never made enough. My wife made all the money.”

That would be Susan, the Native American girl he fell in love with in 1988 when they were both working a carnival in Albuquerque. The next year the couple traveled with the carnival for a season. By the time it shut down that winter, Susan was pregnant.

They’d saved enough to rent a house, but neither had work. Their son Robert was born in June 1990. Jonathan followed in January 1993, and a daughter, Raylene, in April 1999.

In 2000, the couple split. He says he’s not able to visit his kids because his ex-wife will call the police if he comes around. I don’t ask why. The divorce and its aftermath clearly continue to haunt him.

He’s been on the streets ever since.

He hasn’t seen his children in more than a decade, nor has he met his two grandchildren.

Whiteley’s life had been on the upswing before his health began “going crazy,” he said. He was still unhoused, but he had a car, a PT Cruiser, and was making deliveries for DoorDash. For four months he chipped away at the $1,500 a friend had loaned him to buy the car and had finally paid him back. He had $3,000 in the bank. Things were looking up.

But soon after the assault, the pain in his mouth became debilitating. Then his savings were depleted because he was unable to work. The church where he’d been parking his by then broken-down car and sleeping overnight told him he had to move. With his money gone, he took the church up on its offer to give his car to a charity.

“Now I’m sleeping on the ground with the bugs, with open wounds,” Whiteley said. “So, we’ve gone from compassion to torture … overnight.”

Whiteley’s only vices are cigarettes and “too much coffee,” he said, belying the stereotype of the unhoused person as addicted and/or mentally ill.

“There aren’t many around who aren’t addicted to drugs and alcohol, or aren’t mentally ill,” he said. “The majority of [unhoused persons] are.”

With 22 hard years of street life behind him, he has a unique perspective on how to effectively approach the epidemic of unhoused Americans.

Start by “Going back to square one and getting people out of their destructive habits, their addictions, their psychological hang-ups, things like this,” he said. “Once you get people out of that, where they can function, then you can offer them the chance to be productive. That’s the only thing I know that makes any sense that might work.

“You’ve got to treat the problem first, then you can develop the person.”

Temporary housing, with beds for the night and a shower, is no solution, Whiteley contends.

“They don’t realize that developing the person is the only permanent solution. Otherwise, you’re just sticking a Band-Aid on the cancer, and it doesn’t do any good because the cancer never goes away, it just spreads and gets worse.”

He believes getting people off the street should start with having them work for housing and meals.

“Give them a bit of a transition, and then start giving them a paycheck, then start educating them,” Whiteley said. “If we’re going to change things, go all out.”

I asked him what housed people have wrong about the unhoused community.

“The way I see it is anybody who takes the time to pay attention to what’s going on will learn something,” he said. “Most people don’t do that, because then they don’t want the responsibility that comes with it.

“It’s a social problem. It’s nothing else. You’re not going to change people’s minds if you want to be blind. That’s all there is to it.”

With midday temps approaching 100 degrees on Monday, Whiteley and I stepped out on to the sidewalk in front of the Coffee Bean and Tea Leaf on Indian Hill. As he squinted against the sun, his black open wound appeared even more alarming.

I shook his hand and told him he was quite the fighter.

“I have no choice,” he said. “If I stop, I’m dead.”

Courier Distribution/Publications Manager Tom Smith contributed to this story.

1 Comment

Trackbacks/Pingbacks

- Readers comments: August 26, 2022 | The Claremont COURIER - […] Claremont to the test Dear editor: Thank you so much for writing your story about Cash Whiteley. It’s bad…

Submit a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Thanks so much for this story, Mr. Rhodes. I appreciate knowing the personal stories of our unhoused neighbors. Perhaps knowing more will help all of us who are housed and not beset by the kinds of trouble he has faced and continues to struggle to deal with find ways to assist them.